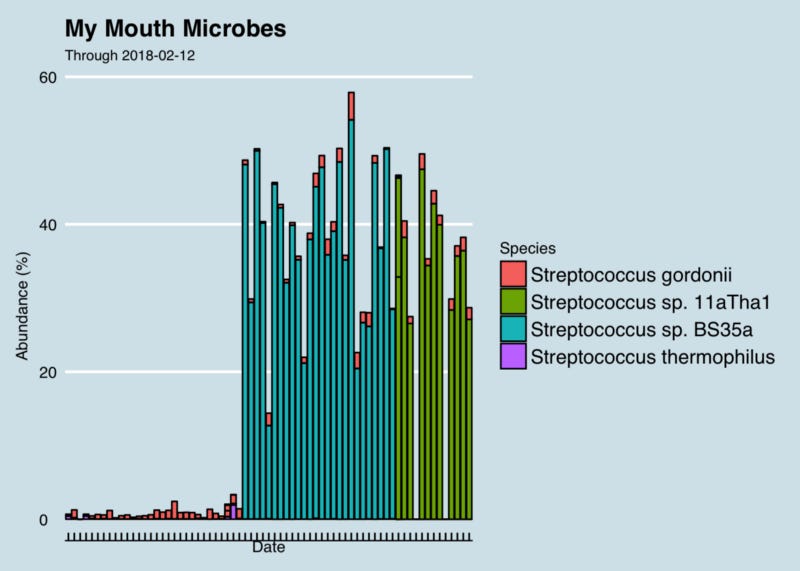

Regular testing of my microbiome often yields unexpected surprises, and this one has me stumped. Beginning in December 2016 and for no apparent reason, my mouth was colonized suddenly by a particular species of Streptococcus that had not been there before. Why? I’m not aware of any major lifestyle or other changes to cause this: same toothpaste, same living conditions. A few dietary experiments here and there, but nothing that coincides with these changes.

Something’s changing in my mouth.

I confirmed with the lab that it’s not contamination.

What’s especially odd is that I experienced a shift like this twice now in one year. After comfortably floating along with Species Streptococcus sp. BS35a for more than six months, suddenly in August the balance shifted again, this time to Streptococcus sp. 11aTha1. Will it shift again? Who knows?

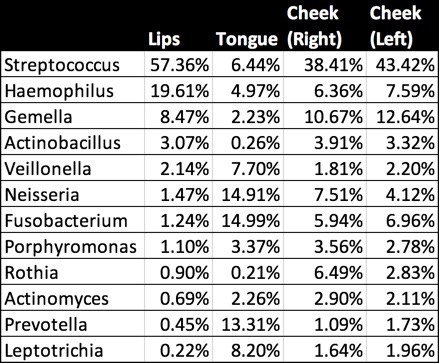

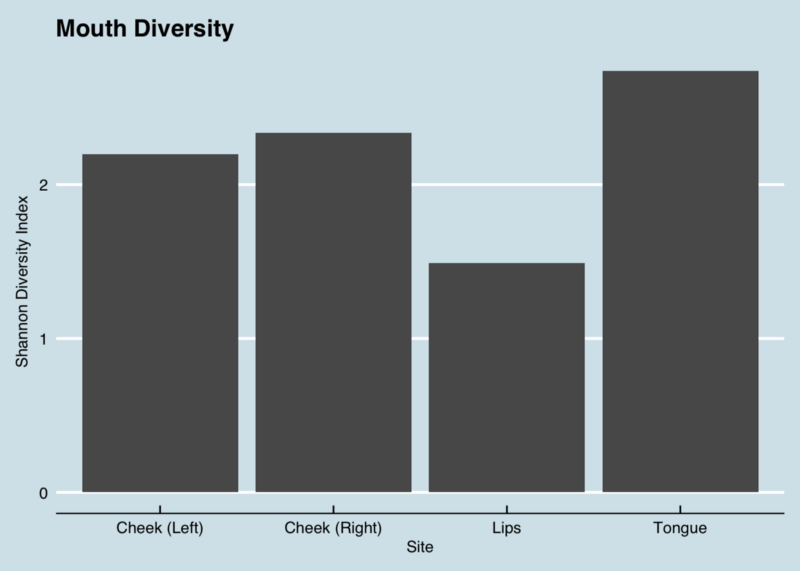

To microbes, your body looks like a hollow tube: skin on the outside, gut on the inside, and a mouth to allow passage between the two. Like purgatory, the mouth is a gatekeeper where new microbes wait before being whisked into the heavenly warm breeding grounds of the digestive system. But it’s no easy waiting room either — the mouth contains many highly-distinct eco-systems, each as different from one another as the Sahara desert is to the bottom of the ocean. Most microbiome and genetic tests ask you to swab the inside of the cheek — an easy, straightforward place teeming with bacteria, but the bacteria in the cheeks can be very different from those on the tongue or the lips. I tested them all one morning right after waking up.

Different microbial abundances at distinct parts of my mouth

Notice how the abundances differ from location to location. As you might expect, the richness and variety of microbes differ as well, with the least diversity on the lips, cheeks about equal to one another, and the tongue (which goes everywhere) the most diverse.

Microbial diversity varies by location.

Earth’s atmosphere was originally void of oxygen, a poisonous gas to the first, so-called “anaerobic” bacteria who thrived precisely because there was no oxygen. Over eons, as oxygen levels increased these microbes found places to hide: deep, dark pockets inside multicellular creatures who traded an oxygen-free interior for the abundant, exotic metabolites the microbes could synthesize. In humans, these bacterial safe-houses begin in the mouth, where the oxygen is low enough to keep the lights on for the anaerobes, while allowing occasional blooms for the aerobic bacteria that thrive whenever the mouth is open and they find fresh air.

Most of them do apparently need moisture: your salivary glands, strategically located in your cheeks and at the bottom of the mouth, churn out 1–2 liters of saliva per day.

The complexity of the mouth microbiome is compounded by the variety of surfaces, hard and soft, each with its own propensity to allow the formation of biofilms, tenacious clusters that protect microbes against invaders. On teeth, we call it dental plaque, a favorite protective breeding ground of Streptococcus mutans, the cavity-causing villain that, once established, is hard to dislodge. I’m fortunate that my mouth microbiome appears to have none of this and it’s true that I never have cavities. I’ve seen levels as high as 2% in some people, who have to visit the dentist no matter how much they brush.

Oral microbes may also play a role in regulating levels of nitrite, which may explain intriguing links between poor oral health and cardiovascular disease.

Most microbes go down the hatch to the stomach, of course, but overly-aggressive tooth brushing or dental work can let a few can sneak into the bloodstream directly, where they can find their way to the lungs, the liver, or the heart, sometimes with deadly consequences. The “viridans” streptococci are one well-studied example: beneficial in the mouth, they outcompete other streptococcus enough to prevent strep throat, yet are the leading cause of heart valve infections if they make it into the bloodstream.

These mouth microbes have other interesting properties that may affect much more than we think. When scientists added an odorless compound from wine to a culture of known oral bacteria, the bacteria generated compounds that we can smell: terpenes, benzenic compounds and lipid derivatives. Each of us has a unique oral microbiome, and the experimenters were able to show that this inter-person variability is large enough to explain at least some of the differences in how each of us perceive a glass of wine.

So what about these odd new ones that showed up in my mouth?

I’ve looked up their names in every reference I can think of, but have found nothing. That’s not too surprising: about a third of oral microbes are known only by their gene sequences. The most satisfying answer from a microbiology expert I consulted is that these are likely to be “passenger microbes”, doing nothing in particular helpful or harmful.

In other words, like so many other microbes in our environment, they are just along for the ride.