Watching Microbiome Changes in Mexico

People are not the only foreigners you meet when you visit another country. Trillions of new microbes, mostly bacteria, will meet you as…

People are not the only foreigners you meet when you visit another country. Trillions of new microbes, mostly bacteria, will meet you as soon as you cross the border, and many of them won’t get along with the trillions that already inhabit your body. Fortunately, as I discovered on a recent trip, Mexican microbes are pretty friendly, and with all the tasty food available in the country, they’re lucky too.

“Montezuma’s revenge” is the popular name given to Traveler’s diarrhea, apparently because somebody got sick in Mexico long ago and decided to pin the blame on the Aztec emperor who was killed by the Conquistador Hernán Cortés in 1520. Whatever you call it, studies show up to 50% of international travelers suffer some trouble, and about 80% of the time the culprit is a bacterium.

Mexico City has become a serious foodie capital. If you haven’t been there recently, many seasoned travelers suggest you check it again because there has been quite a boom in fine restaurants with tasty dishes from around the world. We ate everything, from queso oaxaca at Mercado de San Juan, to the grasshopper-like insect delicacy ( 60 pesos/100g) chapulines, to the wonderful buttery-tasting fruit called cherimoya.

My favorite drink was pulque, a fermented concoction made from the sap of the maguey (agave) plant. Unlike other fermented beverages like kombucha or beer, the fermentation takes place inside the plant, before harvesting. The plants take more than a decade to mature, and when they start to produce, you have to suck out the pulque quickly or it goes bad. Nobody’s figured out how to preserve it without losing flavor and potency, so unfortunately I’m not able to get any in the U.S.

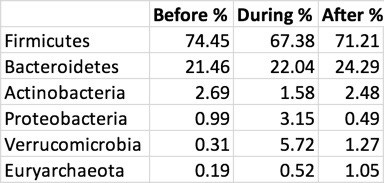

I loved the food, but what about my microbes? To find out, I tested myself before leaving, immediately at the end of the trip (‘during’), and then a few weeks after returning (‘after’). Here’s the highest level (phylum) summary of the most common bacteria I found:

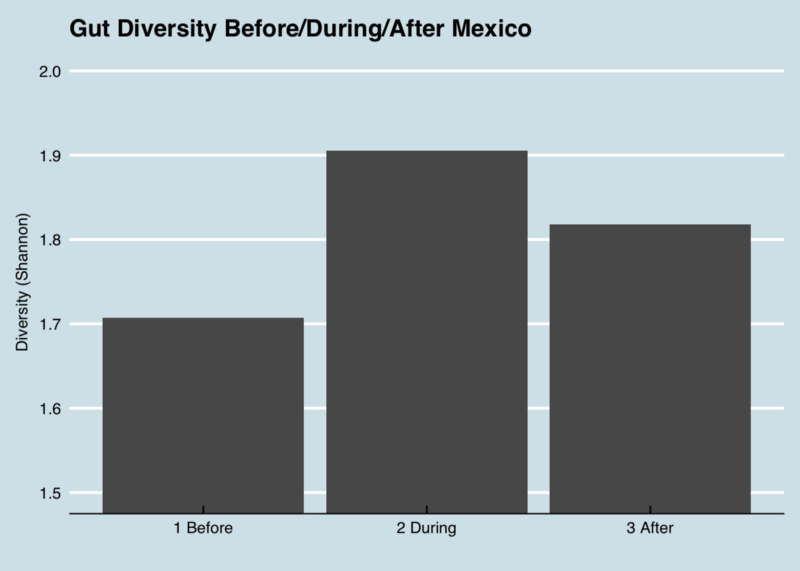

The first thing to notice is the contrast between my microbiome during the trip versus otherwise. Before and after, my gut is normally dominated by the top two phyla, with nothing else breaking higher than 2%, but during the trip the abundances are more evenly spread. In other words, the diversity increased, as you can see in this picture of the changes in my “Shannon” diversity metric:

It makes sense that diversity would increase on a trip, but what can I learn about the bacteria that changed?

Notice how a key one, Proteobacteria, spiked during my trip and then returned to normal after I returned home. I saw the same spike after my jungle trip, during my gut cleanse experiment, and once before when I had been fighting an upset stomach. My experience is consistent with a similar observation by Duke University’s Lawrence David and collaborators, who found that this phylum seems to increase during episodes when the gut is under attack, like it is in foreign travel.

Whenever I see elevated Proteobacteria in somebody’s results, I always ask them if they’ve noticed anything unusual tummy-wise. This phylum contains most of the well-known pathogens, including Salmonella, E. Coli, as well as those responsible for Black Plague and ulcers. Unfortunately the standard (i.e. cheap) 16S rRNA test can’t identify any of these pathogens with suitable accuracy, like the infamous E. Coli or other nasty ones like Shigella. By their nature, pathogens are often very similar to benign or even beneficial bacteria, sometimes differing by only a single base pair. If they were too different, evolution would quickly stamp them out.

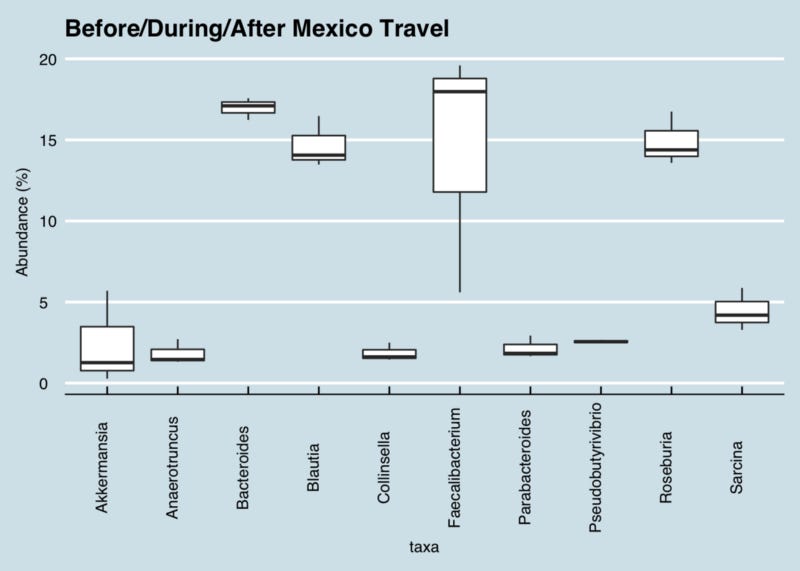

That said, at the bacterial DNA level, the Kluyvera genus is quite similar to interesting bacteria like E. Coli or Shigella, and sure enough, I see that it spiked during my trip. Kluyvera ferments sugars and goes up in people on a ketogenic diet, but in this case I bet I’m seeing evidence of a perhaps some kind of an unwanted invader. (Figure 1)

Figure 1: Box and whisker-style chart showing variability of key genus abundance before/during/after a trip to Mexico. The line through each box shows the median value.

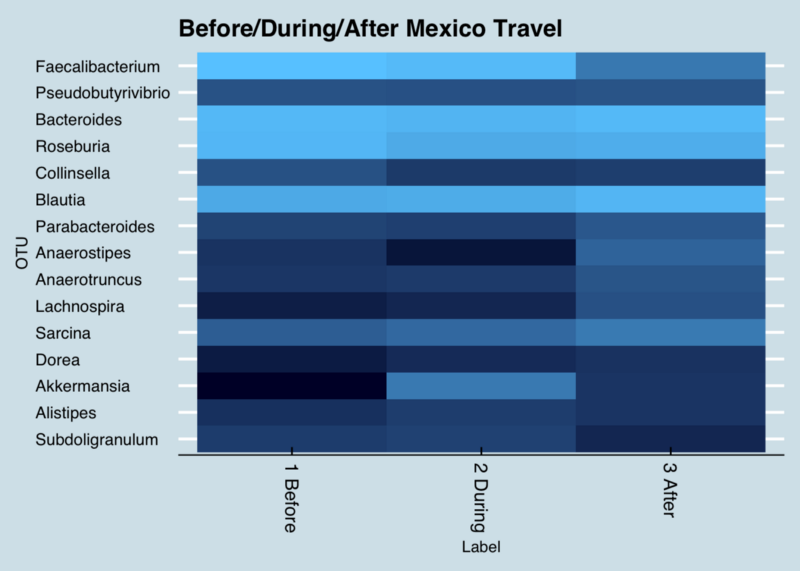

Figure 2: Changes in key genus abundance when traveling to Mexico. (Lighter shades are more abundant)

Next, what might I learn if I study just the bacteria that changed the most ? To do that, I made a list of just those at the genus level that existed before my trip and after, but not during.

Enterococcus, Citrobacter, Methanomassiliicoccus, Fastidiosipila, Acetanaerobacterium

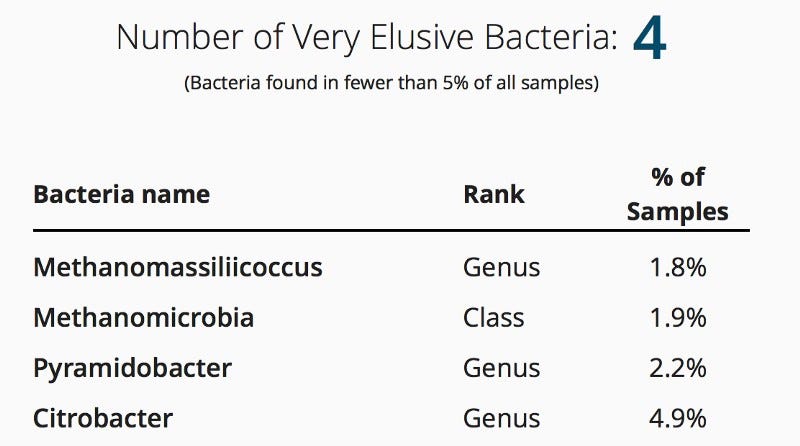

I then compared this to uBiome’s big database, based on tens of thousands of samples. You can find a chart like this on your Insights tab:

Two of these stand out for me: Methanomassiliicoccus and Citrobacter, both of which are rare among uBiome samples and yet they appeared for me just once on a trip to Mexico. Interesting…

I didn’t bother showing the whole chart, but a little further up the list of uBiome database frequency is Fastidiosipila, which again appeared just this once for me.

Next, let’s look at the organisms that disappeared while I was in Mexico:

Turicibacter, Eggerthella, Pseudoflavonifractor, Candidatus Stoquefichus, Acidaminococcus, Candidatus, Soleaferrea, Catabacter, Granulicatella, Varibaculum, Actinomyces, Klebsiella, Asteroleplasma, Sporobacter, Enterobacter

Comparing these to the uBiome database, I see that all of them are pretty common, seen in at least a quarter of all other uBiome users. Again, it’s odd that they disappeared from my results during the trip.

One of them, Pseudoflavonifractor is associated with successful weight loss. I did gain a few pounds during the trip, but lost it all within a few weeks, maybe because this guy resurrected when I got home? Or not. If I’ve learned anything from my tons of near-daily samples, it’s that the microbiome is highly variable and you shouldn’t make big conclusions based on just a single result.

As for the rest, the obvious question– both for the bacteria that I gained and those I lost: is that good or bad?

The answer, frustratingly, is that we don’t really know, but here are some obvious questions for follow-up:

Are these bacteria somehow associated with Mexico? Like other organisms, some bacteria seem to be native to some geographies and some aren’t. Maybe I’ve stumbled upon a few that happen to enjoy the climate there.

I never became sick during my trip. Did some of these new bacteria protect me somehow? If so, what specifically might I do next time to ensure that I can get them again?

Few of the bacteria I gained seem to stick around, but I know from past experience living in another country that it does seem possible to make permanent changes. Many people who live for extended periods in Japan, for example, seem to carry a bacterium that’s good at digesting sushi. Maybe there’s a similar one for Mexican food?

What about the fermented pulque? Is there some specific health benefit I enjoyed by drinking something that thousands of years of tradition says is good for me? Perhaps with more data we can identify exactly which microbes thrive on this stuff.

As a personal scientist, my purpose isn’t to solve these problems right away, but rather to raise new and hopefully interesting questions that others can follow up together. Studying the differences between my own samples is my biggest advantage over “real” scientists, who generally look at anonymous data and rarely have the context to go deep into interesting questions that might not have been apparent at the start of the experiment.

My microbiome changed noticeably during my trip, but it bounced back in a few weeks.

My diversity went up, as you’d expect, as did levels of one particular phylum, Proteobacteria that seems in me to indicate that my body is fighting invaders.

Science still knows precious little about the microbiome, though we continue to learn.

References

David, Lawrence A., Arne C. Materna, Jonathan Friedman, Maria I. Campos-Baptista, Matthew C. Blackburn, Allison Perrotta, Susan E. Erdman, and Eric J. Alm. 2014. “Host Lifestyle Affects Human Microbiota on Daily Timescales.” Genome Biology 15 (7): R89. doi:10.1186/gb-2014–15–7-r89.

Originally published at richardsprague.com on February 24, 2018.