Real scientists are overjoyed to find experimental results that disprove something they or others previously thought was true. But especially in the social sciences, some results — no matter how well-proven — will be greeted less enthusiastically.

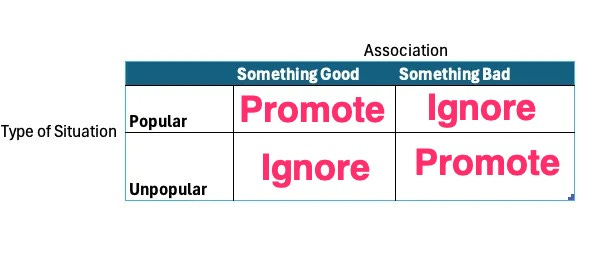

You can summarize the situation with a chart like this:

If a situation is “popular” (e.g. appears to promote a cause that everyone likes) then it’s okay to publicize and promote it. Similarly, the scientific establishment will happily publicize when something bad appears to be associated with an unpopular situation.

Here are some pretty obvious examples where the bias is clear-cut:

Evidence that death counts should be revised up or down for historical events such as the Holocaust, the Chinese Great Leap Forward, or the US-Iraq War.

Good vs bad outcomes in children raised by same-sex vs. fundamentalist Christian parents

Safety and efficacy of routine public health interventions such as vaccination, public sewage control, fluoridated water, or oral contraceptives.

Racial or sex differences in just about anything.

If it’s not obvious to you which “result” is more likely to receive publication and support, you are not qualified to be a professional scientist.

Some of this is presumably explained by Carl Sagan’s comment that “Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence”, which was his own rewording of Laplace's principle, which says that “the weight of evidence for an extraordinary claim must be proportioned to its strangeness”.

But who defines “strangeness”? Research outcomes that seem pretty obvious to me might not seem that way to you.

Let’s look at a couple of examples from the science of men and women, COVID death rates, and recycling effectiveness.

Science of Men and Women

You probably saw that headline last summer with news that women share hunting responsibilities in the vast majority of hunter-gatherer societies. Because any finding will be popular if it obscures innate differences between men and women, this one was widely repeated in all the prestige science magazines (Science, New Scientist, Scientific American, Smithsonian, etc. )

Conversely, when a scientific fact is unpopular, most people won’t see the debunking published this week by a group of anthropologists who found serious problems in the original paper. The errors weren’t minor or hard-to-spot: these were blatantly obvious false readings. Apooria Magazine has a detailed breakdown of the problems, which include selectively filtering data that contradicted their conclusion, no distinction between rare events and commonplace ones or between arms-length assistance and handling weapons, etc. When you read the list of blatant errors, it’s hard to maintain trust in the original editors and publishers who decided to promote this obviously incorrect conclusion.

COVID Death Rates

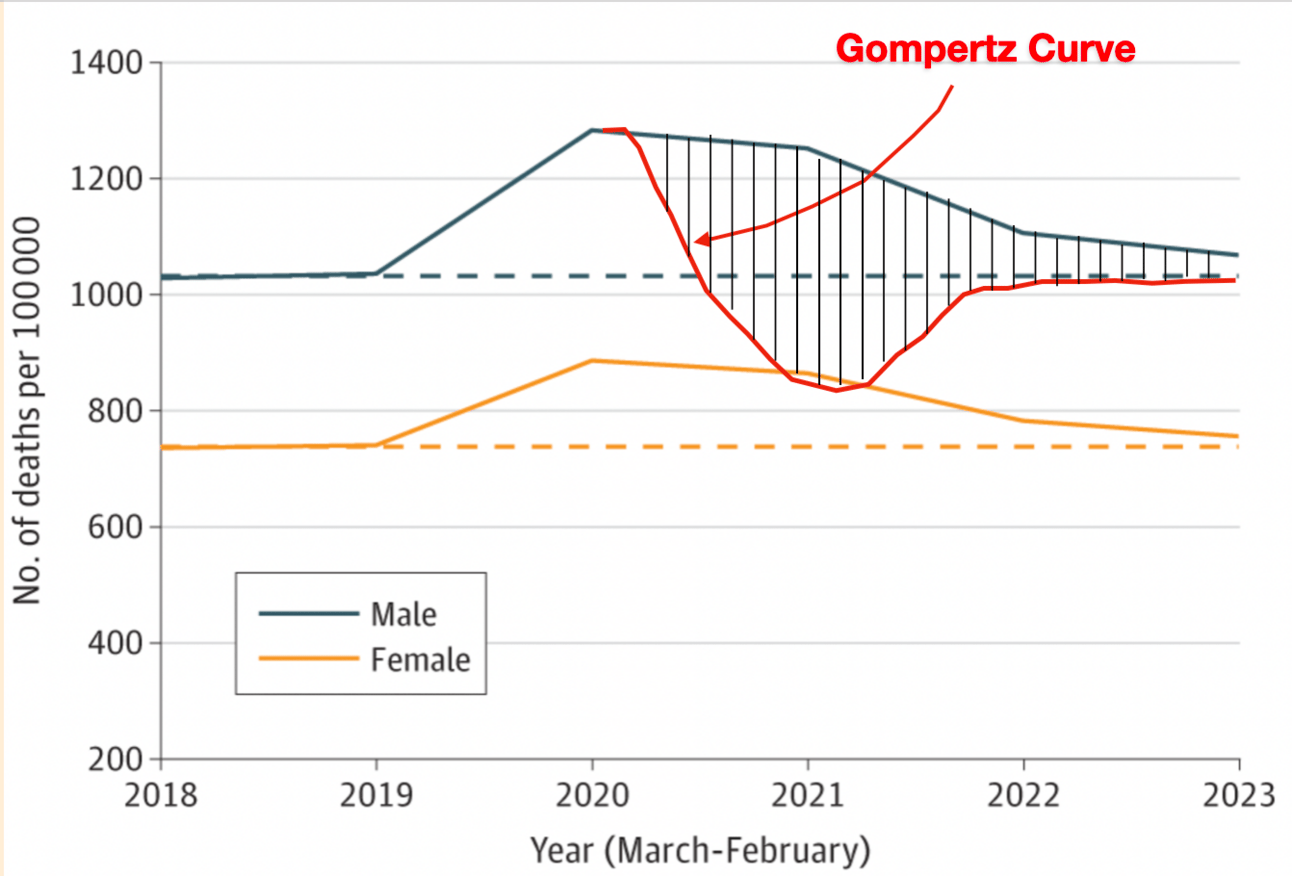

You’ve probably heard that measured in excess deaths, the COVID pandemic ended sometime last year: the CDC and others point to how monthly death rates have reverted back to the average over the past several decades rather than the sharp rise that we saw from 2020-2022.

But wait a minute…wouldn’t you expect death rates to drop for the few years after a pandemic? If the weak and infirm are most likely to succumb to a new virus, then we should have fewer of them in the population now, right? So who are the new people who are dying? The scary answer is that we don’t know, but it could be some combination of (1) preventable deaths that occurred because healthcare was suspended during the pandemic (e.g. fewer cancer exams), and (2) other factors, such as mental health breakdowns, caused by the reaction to the pandemic, or (3) under-studied consequences of mass vaccination.

The Arrow argues that excess deaths are much higher than most people claim, because infectious diseases spread, not exponentially, but along a “Gompertz” curve, which is similar but takes into better account the tail ends of the rise and fall of an epidemic.

Plastic Recycling

Do you carefully separate your garbage to ensure your plastics always go into the recycling bin? What happens after that?

The New Republic summarizes the appalling state of plastic recycling:

Hardly any plastics can be recycled. You’d be forgiven for not knowing that, given how much messaging Americans receive about the convenience of recycling old bottles and food containers—from the weekly curbside collections to the “chasing arrows” markings on food and beverage packaging. But here’s the reality: Between 1990 and 2015, some 90 percent of plastics either ended up in a landfill, were burned, or leaked into the environment.

Another recent study (albeit from a highly-biased environmental justice group) estimates that just 5 to 6 percent are successfully recycled. In addition, they claim that “not one single type of plastic food service item, including the polypropylene cups lids that Starbucks touts as recyclable” are actually recycled.

This aligns with my anecdotal experience from a Starbucks barista acquaintance who tells me that her manager lets her combine the recycling and regular waste into one bin in the back of the store.

Conclusion

These are just a few off-the-cuff examples of how the science you read in the mainstream journals isn’t necessarily representative of the space of true things that could be reported. Conclusions gain headlines for reasons beyond a simple assessment of their truth or relevance.

The personal science solution is to remain highly skeptical, but open-minded, especially when your own eyes or intuitions conflict with a formal study. Often it’s the studies that aren’t publicized that are the most important.