Respiratory illnesses are everywhere, and most of us catch a bug or two every year or so.

How should a personal scientist respond when the inevitable happens?

The past five years have been the most healthy of my life, at least for respiratory illness. No colds, no flu. Oh that’s right, I tested positive for COVID for a week in early 2024 but the only “sick” was a headache and some fatigue for the first day or so. No stuffy or runny nose, no coughing, nothing. In my whole life I’ve never gone for so long a stretch without something.

Oops, until last month. It started with a slight cough on a Tuesday night that worsened over the next few days to include all the flu symptoms: achy fatigue, mild headache, and a steadily worsening cough that got bad enough to keep me from sleeping. I pretty much lost an entire week, with just the bare minimum of keeping up with work—remotely—and napping most of my days away.

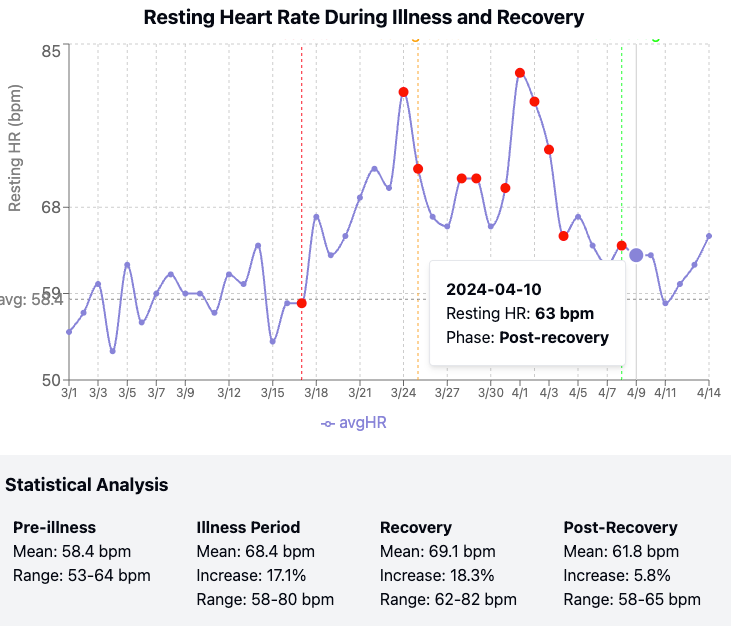

You can see the dramatic increase in my resting heart rate (as measured by my Apple Watch, and compiled to Auto Health Export):

This chart was generated for me by Claude, which I found an indispensable help throughout my illness. (It’s become an indispensable help to the rest of my life too, of which I’ll write more in future posts).

As detailed in PSWeek250410, I’ve set up a Claude “Project” that contains all my medical information—my various lab tests from Function Health, SiPhox, a table of my self-tracking notes, and even my Dexa Scans. Anything related to my health—I just throw it in—PDF, text, spreadsheet, format doesn’t matter. Whenever I have a health-related question, I ask that Claude project, which tailors the answers to my specific situation.

For example, on the night when I felt that first cough, I asked whether it was better to go full-on hibernate or do a limited workout to stimulate my immune system (It said do the workout at 70-80% of usual intensity), and when I started to feel worse should I take something (Acetaminophen is best for my kind of liver), and what about cough relief (don’t take Nyquil – use plain Dextromethorphan, like the kind in Delsym).

I also found Claude to be spot-on for predicting the symptom progression, including an accurate date when I would feel better (7 days, but 3 weeks for the cough). When I (stupidly?) felt better enough to travel, it justifiably reprimanded me, but pointed out that the extra exertion was likely the cause of my continued suffering and not something more serious like pneumonia.

If you’re a hypochondriac like me, illness is a time of reflecting on all the potential bad things that can happen, so I found my AI Chatbot a welcome reassurance. (and my doctor is no doubt relieved that I didn’t pester him with my technical questions).

Bottom line: get yourself up to speed on the latest LLMs and don’t stop.

Personal Science Influenza Readings

To answer your first question: no, I did not have a flu shot this year. Was that the reason my five illness-free years came to an end? I’m skeptical.

The CDC says that only about half the H3N2 viruses show an antibody reaction to the vaccine and even then it’s unclear whether it prevents infection.

The highly-respected Cochrane Review ended their studies of flu vaccine in 2018 because they concluded it’s a waste of time. If the vaccine has an effect, it’s impossible to detect. Statistically you might prevent one case if you vaccinate 71 healthy adults, but you might also make them more susceptible to other illnesses. Check this 2019 Dutch study, which compared real flu shots to placebo among a thousand elderly people who were followed for twenty-five years (!). The shots made no difference in life expectancy. A large US study from 2005 concluded the same thing: “We could not correlate increasing vaccination coverage after 1980 with declining mortality rates in any age group”.

Worse, maybe the flu vaccine makes it more likely you’ll get sick? That’s what researchers at the Cleveland Clinic recently concluded in their 2024-25 study of 40,000 employees. For what it’s worth, I don’t believe that paper’s conclusions: Statistician William Briggs shows the many failings of the research, like how vaccinated people are more likely to get tested for flu (and conversely, unvaccinated are less likely to see a doctor). Undoubtedly whatever effect the vaccine has, it was overwhelmed by these confounders.

Still, you’d think that for something given to tens of millions of people each year, the evidence would be stronger one way or another.

Finally, if you find yourself in the early stages of what seems like the flu, please immediately contact the SNIFLS study conducted at the University of Washington. The Chu Lab at the Division of Allergy and Infectious diseases will send you a nasal swab that they want you to return for analysis. Sign up here. (Unfortunately I was too late—you have to do it within a few days of symptoms appearing).

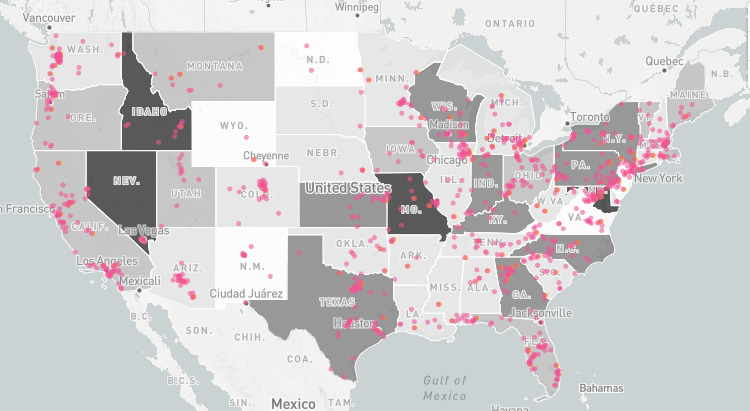

And if you’re not already doing this weekly, please join 7 million other people at Outbreaks Near Me to report your status. I get short two-question email every Monday that I’ve been answering for years. Here’s where people have been reporting the flu this week:

Personal Science Calendar

If you’re in Seattle this weekend, please join me for a discussion on “Healthy Humans of Seattle: Microbiome”. Sunday afternoon April 27th: (RSVP here)

Also, Bay Area residents please join us May 5-8 at the Global Synthetic Biology Conference. Our friend Jocelynn Pearl is leading a session on DeSci and the future of biology and biohacking. I’ll be there the whole week, so let me know if you have time to meet.

And don’t forget to crack open your iNaturalist app from April 25- April 28th for the City Nature Challenge. Hundreds of cities around the world are participating: go around your neighborhood and log plants. Remember that your photo uploads help power the wonderful iSeek app that has revolutionized the way most of us identify plants.

About Personal Science

During the COVID pandemic, most health-related posts on YouTube, Spotify, Facebook and most other platforms attached a warning to only trust the official government websites from CDC and at https://covid.gov.

Now those official sites have been updated, and many news outlets issue the opposite warning: don’t trust these same sites. Huh?

Personal scientists are skeptical about everything, so we aren’t bothered by this apparent flip-flop. We were skeptical then, and we’re skeptical now. But that’s not an excuse for giving up. We have to believe something. The question is how to decide.

Economist Arnold Kling says “we decide what to believe by deciding who to believe”. Maybe you trust “our democratically elected government” and the (presumably neutral and science-minded) people they appoint at FDA, CDC, and other regulatory agencies. But you also trust other reputable organizations and their leaders. What do you do when your trusted sources disagree with one another?

Personal science says there’s only one way out of this conundrum: learn to apply the techniques of science to your everyday situations. Philosopher of science Michael Strevens summarizes this as a trust in (1) raw data, (2) good collection methods, and (3) logic to tie it together. (See PSWeek221229)

This newsletter is a weekly summary of ideas and techniques that we hope will help others who want to get better at personal science. If you have additional thoughts or topics you’d like to discuss, please let us know.

P.S. Why did I go so long without the flu? Mostly I think I was lucky, but the one habit I changed since 2020 was that I wash my hands way more frequently. It’s the only intervention that, according to Cochrane, “is likely to modestly reduce the burden of respiratory illness”.