Personal Science Week - 250403 23andMe

What 23andme could have been, plus useful methods for today

The recently-announced bankruptcy of 23andme was long in coming but for many of us was the disappointing end of a very promising era.

For personal scientists, it’s a cautionary tale but with an inspiration to continue to push for wider access to cutting-edge technologies.

Back in 2007, I jumped at the chance when I heard about a new company that could provide me access to information about my own DNA. After the Human Genome Project brought genomics to public attention, many of us curious outsiders wished we too had access to the same lab technology that professionals were using to unlock genetic data daily. 23andme became one of the first to offer that access to everyone at reasonable prices.

Now co-founder Linda Avey on X writes her personal history of 23andme, which she originally intended to be exactly what those of us in personal science want: a general-purpose site where individuals can do much more than DNA:

I didn’t want to stop there. I knew we needed to keep engaging with our customers. What if we added in symptom tracking, blood test results, drug response, environmental exposure, etc? There was a wealth of information our customers could share. When we launched our initial surveys, we were pleased and surprised at the high response rate. But surveys can only collect limited data. There were so many other ways to dig deeper. And from a business model perspective, the one-and-done DNA collection step wouldn’t cut it.

After 2009, Avey found herself sidelined as the company put more emphasis on deals with Big Pharma, significantly raising 23andme’s paper value but shifting away from its mission as a “category-defining Google of digital health.” She became a private investor in many other healthtech companies and remains a valuable voice for personal scientists.

Christina Farr says 23andme raised too much money, reaching a stratospheric multibillion dollar valuation on hopes of becoming a major player within the Pharma industry, but ultimately just didn’t have data worth that much.

As an insider to similar discussions at similarly failed pioneer uBiome (“the 23andme of microbiome”), I think this is a common problem. Personal science companies can be profitable, but the timing has to be right and meanwhile the expenses need to be tightly controlled. Becoming “the Google of digital health” is not something that will happen before the public is ready. Meanwhile, it’s more important to focus on the product and the science—find ways to make the product genuinely useful before you invest too much in expansion. 23andme “lost its way” when it tried too hard to make itself appealing to the professional scientists, when it should have focused on the rest of us.

Evolving with Nita Jain

We’ve mentioned Nita Jain previously in Personal Science Week for her original, in-depth takes on issues related to chronic disease and more. I was honored to be on her podcast, published recent. We talked about a lot of interesting issues related to personal science.

Here’s one excerpt:

One of the most important lessons from Sprague's exploration is that microbiome testing requires multiple samples over time. Our gut bacteria undergo significant shifts even within a 24-hour period, making single-sample testing misleading.

A one-time gut check might capture an unusual day rather than represent an average of your typical microbial makeup. This temporal variance means that meaningful microbiome understanding requires tracking changes over time rather than fixating on a single snapshot. For accurate assessment, longitudinal sampling is essential.

When interpreting microbiome test results, be aware of the "compositional problem." When you take a subset of an environment, you're assuming it's evenly distributed and representative, an assumption that isn't always accurate.

Most microbiome tests report results as percentages (scaled to 100%). This creates a potentially misleading picture where proportion is conflated with abundance. If your test shows 5% Lactobacillus one day and 10% the next, this doesn't mean the bacterial population doubled because the context of the entire ecosystem matters.

More COVID

Speaking of resources for chronic disease, our friend Salvatore Mattera has started Help for Long COVID, a well-done site that offers tons of resources for people who still divide their lives into “before COVID” and “after”.

And slightly related to both 23andme and microbiome, evolutionary geneticist Paul Norman, studies bubonic plague at the University of Colorado, Anschutz. In 2021, Norman and his colleagues demonstrated that HLA variants likely played a role in determining who survived medieval plague outbreaks. via BBC The variant, HLA, is related to the ones associated with asymptomatic COVID infection.

Methods in Personal Science

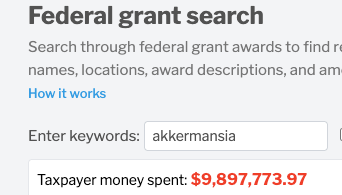

Wondering how much the US Government spends on specific projects? Search this database to find that over 100 grants include the words “personal” and “science”. Okay, not a particularly useful search. But it might be more useful if you are interested in a very specific issue, like say an intestinal bacteria associated with health:

Use your regular Google app with Google Lens to scan that suspicious rash or mole on your skin. No, it’s not a medical diagnosis, but you’ll be matched with similar-looking skin conditions that may help you decide what to do next.

Bellingcat tool: If you know the height of an object in a photo, the length of its shadow, and the time of day the photo was taken, you can calculate the exact spot on earth where the object is. Video shows how.

Don’t want to pay a subscription just to read that one article behind a paywall. PaywallBuster searches all the obvious places (e.g. archive.is) to present links to paywalled content. Another one, OpenRead, is ostensibly for academics who want to comment on PDFs, but you’ll often find papers there that you would ordinary only find through a university subscription.

AI expert Andrej Karpathy has been tracking his sleep and ran his own personal science experiment to compare Oura, Whoop, 8Sleep, and Apple Watch . He concludes Oura is best and that Apple Autosleep is basically a random number generator. I agree, but add that LLMs let you do something even better: keep your own short self-reports and ask an AI to summarize and provide suggestions.

About Personal Science

My new 200-page book Eyes on Health (mentioned in Back in PSWeek250320 ) is now officially available through Amazon and many fine bookstores. The full text is also online, so don’t buy it unless you really want a printed copy.

What made this book interesting was how it was developed: an AI-based workflow that now makes it surprisingly easy to build full-length books out of a collection of notes. If you have your own large collection of notes ( “digital garden”, “commonplace book”, or just a bunch of old blog posts you’re proud of), DM me and let’s see if we can collaborate.

If you have other questions or comments, please let us know.

23andMe did add blood testing, but too little too late...

Will you be signing books at the next QS Seattle meetup? 😉