When we think about eyes, we typically focus on vision—how well we can see the world around us. But did you know your eyes reveal much more than just what's in front of you? The human eye, particularly the retina, offers a remarkable non-invasive window into your overall health.

This week I summarize what I’ve learned from taking regular high-resolution retinal photos of myself.

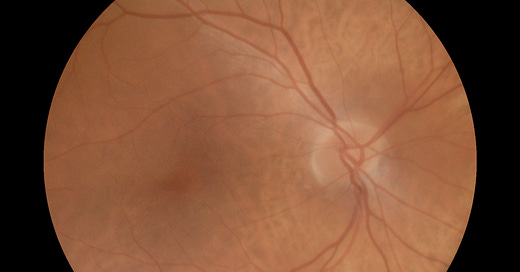

Your retina isn’t just the light-sensing tissue that helps you see. It’s actually an extension of your brain, sharing the same developmental origin as your central nervous system. A full, deep look into your “fundus” — the medical term for the retina plus the surrounding tissues in the back of the eyeball— offers a real-time peek at living blood vessels, neural tissue, and metabolic activity without any invasive procedures. It’s like having a transparent window into your vascular and neurological systems.

For the past two years, I’ve been helping to build and sell a low-cost, portable fundus camera. Although we designed it to be much cheaper than the $50K your optometrist pays for roughly similar quality, it’s still a few thousand dollars—more than a typical personal scientist will pay—so we primarily sell to health professionals. Meanwhile, it offers a peek at a new diagnostic I’m convinced everyone will use eventually as the prices come down.

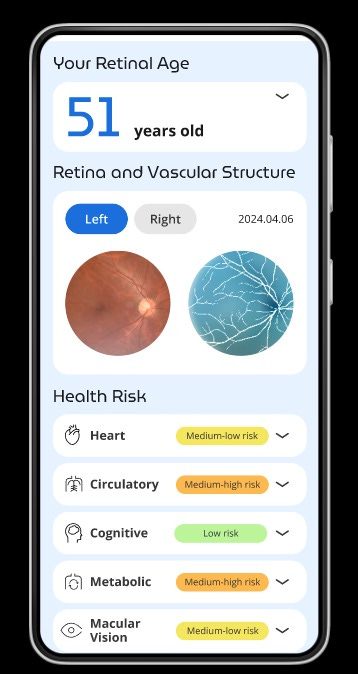

It’s extremely easy to use. After you look into the camera, the computer finds the center of each pupil and flashes a low-intensity light onto the back of the eye while it snaps a high-resolution photo. The images are then uploaded to special servers that run a “deep learning” AI algorithm to compare your eyes to the millions of labeled images we have in our huge dataset. After a minute or two of processing, the AI algorithms generate a brief health assessment that looks like this:

There are dozens of well-done studies that show a link between features of the retina and various health measures. Using some basic, well-understood AI algorithms, many research teams, including Google and a number universities have been able to reliably predict many health attributes by comparing these high-resolution photos to a well-labeled dataset. Our team did something similar, distilling the meaning of millions of real images into a basic health summary across several health features: heart, circulatory, cognitive, metabolic, and macular vision. New photos from our camera are then run through the model to generate an index that shows the likelihood of various health conditions.

So how accurate is it?

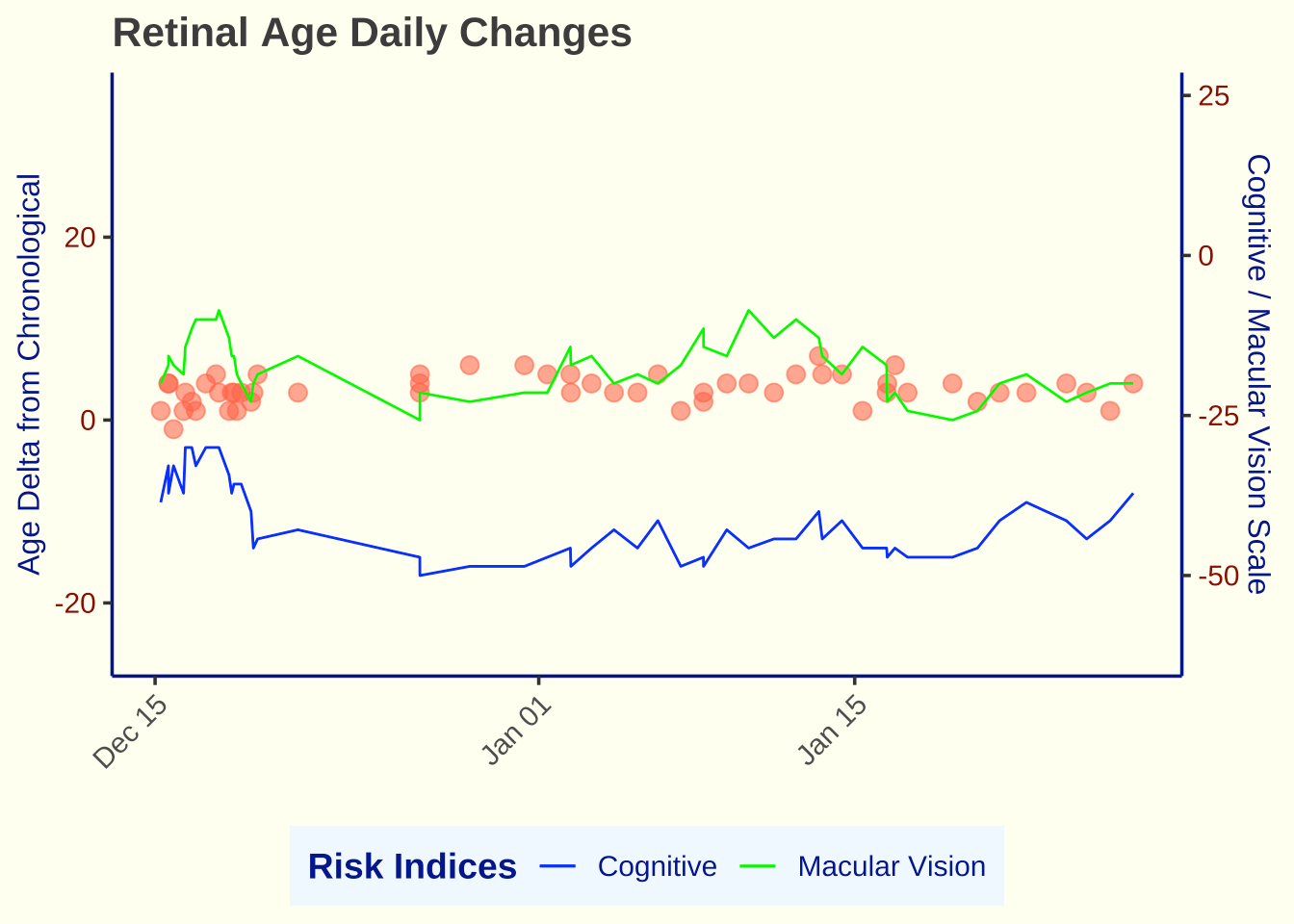

When I test any new diagnostic, I want to know (1) what results does it give if you test it more than once on the same person, and (2) how different are the results for different people. If I test myself twice on the same day and get wildly different answers, I’ll lose respect for the test. Similarly, if multiple people all get the same results, I’ll wonder if the test is really measuring something interesting.

Our camera passes both tests. For example, here’s my (mostly) daily results over a one-month period. The numbers fluctuate slightly day-to-day but not enough to make me suspect a problem with the test.

Incidentally, that slight drop in “Cognitive” in late December coincided with a holiday trip during which I picked up a barely-noticeable respiratory infection. My numbers have thankfully recovered since then.

We’ve found that—for better or worse—the eyes don’t change all that much over time. The final health assessment in the report is a very broad summary of several hundred parameters picked up by the camera, many of which fluctuate wildly day-to-day, probably in response to various daily activities. Ideally, I’d like to follow those noisy parameters to find consistent patterns over time. I suspect we’d find some combination of perhaps dozens or even hundreds of parameters that respond predictably to specific interventions—sleep, food, exercise, etc. If we can crack those relationships, I’m optimistic this can be a useful new tool that, once the prices come down, will be an indispensable part of every personal scientist’s toolkit.

Learning More

Personal Science Week isn’t a sales platform, so I’m not trying to pitch our company or its camera, but you can view the website at https://opticare.ai. Ping me directly and I can arrange for you to get your own test.

I’ll be speaking about this topic in more detail at the Biohackers World conference in Los Angeles on March 29-30. Buy tickets here.

At the conference, I’ll announce my new 200-page book Eyes on Health that goes into much more detail about the eyes and the technology behind AI-powered retina photography. Printed copies are available through Amazon and many fine bookstores.

Speaking of eyesight, have you heard of Irlen Syndrome? It’s a condition where you are bothered by bright fluorescent lighting, or you have trouble reading lengthy passages on white paper. To say I’m “bothered” may be an overstatement—I think of myself as pretty normal— but I took their brief 15-question test and, lo and behold, I should talk to one of their specialists. Supposedly they can match you with precise custom color glasses that can greatly improve your relationship with light and reading. How real is it? I don’t know but I’ve met people who swear by it.

I’m much more skeptical of iridology, an alternative medicine technique that is sometimes confused with my AI-based fundus/retinal AI-based system, though the two are completely different. Like astrology or fortune-telling, you can find people who insists it’s miraculously accurate. Like any personal scientist, I try to keep an open mind but this one is pretty far down the list of stuff I have time to consider for myself.

More Personal Science

Are you in the Seattle area on April 5th? Join Kris Welch and others for a tour of Upgrade Labs. This is a new chain of high-end fitness centers, now in California, Texas, and a few other places including Bellevue, Washington. For about $400/month you get access to all the latest fitness and health tracking toys, including various red light and PEMF therapy beds, metabolic testing and training gadgets, and AI-powered fitness machines that adjust your training level to maximize the benefits from each workout. GeekWire did a recent well-balanced review of the Upgrade Labs experience, that was generally positive, especially about the time-saving aspects, but admitted that not everyone would find it worthwhile.

About Personal Science

Isn’t it curious that the people who seem most worried about “disinformation” are never concerned about their own beliefs, which presumably are true and accurate. Personal scientists, on the other hand, want to decide for ourselves, unfiltered by those who think they need to protect us from wrongthink.

But thinking for yourself isn’t easy. In a complicated world filled with contradictory advice from arrogant “experts” who often disagree with each other, finding clarity is hard. There may be no perfect solution, but we believe the scientific method offers a glimmer of hope. Be open-minded yet skeptical. Trust what you can measure and observe firsthand, and always be brutally honest in acknowledging that you are often the easiest person to fool.

We publish thoughts and ideas about personal science each Thursday. If you have other comments you’d like to discuss, please let us know.