Personal Science Week - 250116 Context

Better understanding the context of your situation is half the solution

When applying science to everyday life, much of our response depends on context. The difference between an inconvenient sniffle and fatal pneumonia depends critically on other symptoms, and of course the age and other health conditions of the sufferer. It’s all context.

This week we’ll look at some consequences of context.

If you suffer from a chronic condition, one of your first struggles is simply how bad is it? What is the precise version or name of this disease? What makes you different from a healthy person, or from the healthy person you used to be? Are there other people with the same condition, and if so, how does your situation compare to theirs? Are you getting better or worse?

In other words, you want to know the context. The first step in any treatment plan requires that you understand how you compare…to healthy people, to those who have the same condition as you do, to people who have partially or fully recovered. Are you improving or deteriorating?

Even symptom tracking is just one aspect of the question of context. I want to know more precisely the conditions under which my problem gets better or worse. In other words, what is the context? (e.g. are my migraines triggered by high altitudes, by caffeine, by stress, by something else? All of these are just other ways of saying “context”).

Context Examples

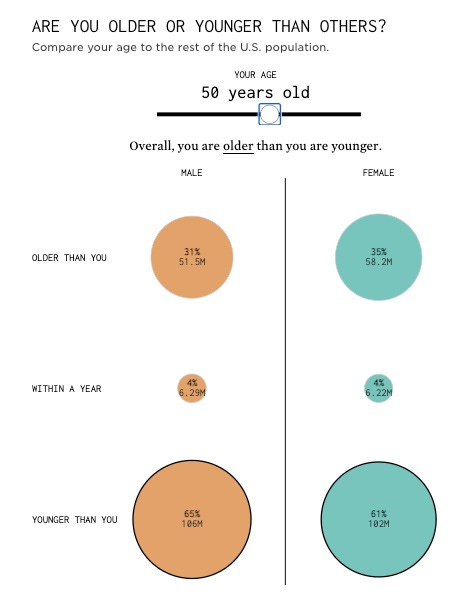

Are you old or young? It depends on who’s doing the comparing.

Compare yourself with this interactive plot

How about how you spend your time? Are you a late riser or a night owl? Do you eat dinner early or late? Those questions are answered by FlowingData statistician Nathan Yau, who computed this from the American Time Use Survey, which let you download lots of statistics about daily life via IPUMS

But don’t just compare yourself to other people. Compare yourself to yourself — under different conditions, and over time.

Eric Topol summarizes a recent Nature paper on those comprehensive metabolic panels that you get with any standard blood (CBC) test. Rather than use reference ranges for things like RBC, WBC, or the other numbers in the results, the authors show you’ll get more revealing insights by focusing on the intra-individual1 variation. In other words, you may get more predictive value by looking at changes in your own results over time than by simply comparing your results to the averages of other people.

Disease and Context

Our friend Nita Jain has been on a roll with her Substack “Evolving”, where she digs into chronic disease and potential treatments. In her M5 Medical Manifesto she reminds us that living organisms are massive communication networks, where every signal counts.

We are living, breathing ecosystems consisting of thousands of complex networks that relay millions of signals every day. And our bodies speak a wide array of molecular languages including Notch, Jak-STAT, Hippo, and Hedgehog. Our gut microbes communicate amongst each other using languages like quorum sensing, and they communicate with us through toll-like receptors (TLRs) and gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT).

When you classify a set of symptoms with a specific label (e.g. “cancer”, “pneumonia”, “Alzheimers”) you are over-simplifying an extremely complex process of a massive network responding to what might be a whole series of breakdowns. A treatment that addresses the symptoms might have subtle consequences elsewhere. Medicine of the future, she says, should think more carefully about a “methodical, order of operations” approach that proceeds step-by-step through a whole series of protocols that can unwind the communication breakdowns that caused the problem in the first place.

Nita has thought through more consequences of what it means for a living organism to be a bunch of networks within an embedded environment in which they function, including why cancer is not caused by mutations. Highly recommended reading.

Speaking of Diseases

A new company Every Cure has a $48M government contract to build a drug-repurposing database and algorithms that patients, doctors and researchers can use to find drugs for untreated diseases.

[Dr. David Fajgenbaum, an immunologist now at the University of Pennsylvania] studied his own blood samples for clues to a drug that could tamp down his immune system and stop relapses. He figured out that sirolimus, a drug used to prevent transplant patients from rejecting a new kidney, might keep his disease in check. Fajgenbaum, 38, takes the drug every day and has been in remission for 10 years.

If you’re a personal scientist looking into disease, it helps to know all the pathologies that are out there. Malacards is a database that lists about 20,000 human disease. I tried “Volvulus” and it gives a bunch of details, including associated genes and various drugs.

About Personal Science

Meaningful insights about ourselves or our world often come not from comparing ourselves to population-wide averages, but from carefully tracking our own variations over time. That’s one of the principles of what we call “personal science”, where we take seriously the motto of the Royal Society, established in 1660: Nullius in verba (“take nobody’s word for it”).

The scientific method gives us tools to understand these patterns, but it requires both patience and precision. Complex networks of symptoms and signals are rarely reducible to simple labels or one-size-fits-all solutions. By maintaining careful records and staying curious about our own data patterns, we can uncover insights that even experts might miss.

If you have ideas or experiences to share, please let us know.

An earlier version mistakenly said “inter-individual”, which is incorrect. (Thanks to reader Julie Claire Green ND for the correction!)

Something doesn’t seem right about this statement about the nature article:

"The authors show you’ll get more revealing insights by focusing on the inter-individual variation. In other words, you may get more predictive value by looking at changes in your own results over time than by simply comparing your results to the averages of other people."

Although they look similar, the prefix intra- means "within" (as in happening within a single thing), while the prefix inter- means "between" (as in happening between two things). (Merrian-Webster).

So perhaps it should say, “ you’ll get more revealing insights by focusing on the INTRA-individual variation.”

The article behind a paywall, so I did not go the original source to see what is said.