Personal Science Week - 241212 Food Labels

The case against nutrition labeling and why alternatives are better

Personal scientists love quantitative information. Food and nutrition labels seem like a great example of something we should support and encourage. But should we?

This week we look at the case against mandatory nutrition labeling and why the alternatives are better.

The Case Against Nutrition Labeling

RFKJr and the “Make America Health Again” (MAHA) people point to the ways that US food manufacturers get around food labeling requirements to add ingredients of questionable safety. You’d think that a personal scientist would be in favor of better, more accurate label requirements Transparency is good, right?

Manufacturers have been required to list ingredients since passage of the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act in 1938. But the detailed nutrition labels you see today are more recent. Calorie counts have been included only since the 1970s. It wasn’t until 1990 that the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act standardized information like calories, fats, cholesterol, sodium, carbohydrates, and certain vitamins and minerals. Given the rise in obesity and chronic illness since then, it’s hard to argue that these laws have improved health.

The problem with mandatory one-size-fits-all labeling is that it’s, well, one-size-fits-all. People who care about dietary cholesterol, for example, can see that on the label. But what if you care about, say, Omega-6 content?

Or what about the silly notion of “serving size” that applies equally to a 90 pound diabetic grandmother as it does to a 20-year-old 250 pound professional football player? Does a pregnant woman need the same “Recommended Daily Allowance” as an elderly man suffering from stomach cancer? Yeah, yeah, these distinctions are noticed in the fine print for people who bother to look into it. But who does?

Labels are less accurate than you think

Like any good personal scientist, you probably think the extra information in a label is nice to have. But what if the information isn’t accurate?

It’s surprisingly easy to create a legal food label.

Maybe you imagine that every food manufacturer submits a sample to a professional lab that comes back with a carefully-calculated result. While bigger manufacturers do that (and have legal teams to ensure they follow the letter, if not the spirit, of the requirement), who knows what you get from the other products you consume. Yes, labels are required for just about anyone (there are exceptions if you sell under 100,000 units per year, or have fewer than 100 employees), but the FDA rarely checks.

And no, it’s not that hard to make a label. In most cases, you just fill out a web form. You can make your own, legally valid nutrition label right now with NutritionPro software ($39/month, or just use their free trial). Although I doubt that many manufacturers deliberately lie, it’s essentially an honor system.

The labels are probably wrong anyway

The FDA allows your label to be off by as much as 20%. When New York Times “Calorie Detective” Casey Neistat did lab testing of five items purchased on a typical day, he found the labels underestimated the actual values by more than 500 calories! With those error bars, imagine how much off you’ll be at the end of a week.

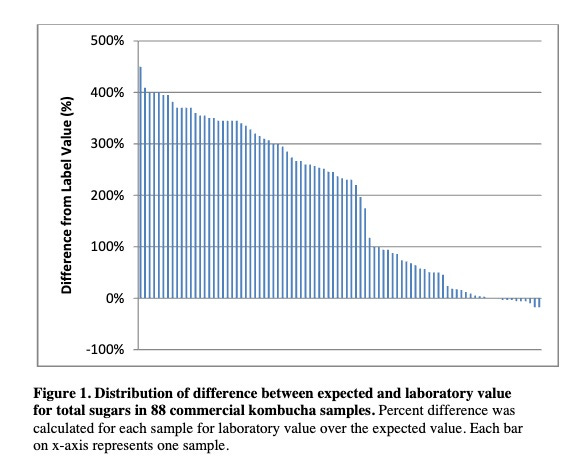

When NaturPro Scientific analyzed 88 different kombucha products for actual sugar content, they found major differences with their labeled values:

There are many more examples. If you depend on the manufacturer labels alone to guide your nutrition information, you can be seriously wrong.

A Better Solution

Maybe mandatory food labeling made sense back in the pre-internet/smartphone days when it was too difficult to look up the information yourself. But now that we’re all just a barcode scan away, why not get rid of the labels entirely and let people look up exactly what they want?

Ironically, one reason these apps aren’t more popular is because the government requires the current labels, so most people don’t know that there’s a problem with accuracy. Who needs an extra app if the government requires all that information for free?

Harvard law professor Cass Susstein reminds us that, although most Americans think that, sure, labeling laws are a good idea, but it’s for other people, not themselves.

an overwhelming majority of Americans favor a federal mandate requiring restaurants to disclose the calories associated with their offerings (Sunstein 2016). Many people who favor a federal mandate apparently believe that they themselves will not benefit from the information – and may even be harmed by it (Thunstrom 2019; Thunstrom et al. 2016). They want their government to require disclosure of information in which they have no interest (or which they would prefer not to get at all).

In other words, few people would mind if the labeling requirements were ended. And for people who do care, there is no shortage of apps that would rise to fill the gap for people who want accurate, personalized information:

For example, Sift and Fig are two great apps that provide much more detail about your food than you’ll get from the label alone. Just scan the barcode and these apps will tell you in-depth information personalized to your own needs. Do you care about gluten? Ingredients legal in the US but banned elsewhere? The app will tell you. Plus you can personalize it for your own dietary requirements, with special consideration to people looking to advice for, say, paleo or keto diets or for conditions like IBS or food intolerances like nuts or soy.

Both apps offer 5 free scans/month if you just want to try it; If you’re serious about a specific food, then you should just pay the $40/year for the full version.

Incidentally, Fig is expanding to include restaurant meal information and they’re looking for reviewers: Apply here

For More Serious Nutrition Help

Some people have health conditions that require much more detailed information. Personal Remedies offers a food database for chronic conditions: Their team of professionals curate a database of foods, ingredients, and their association to various chronic illnesses.

They also offer a large collection of mobile apps that address specific conditions ranging from IBS to High Cholesterol, that help you decide whether a specific food is okay or not.

Personal Science Miscellaneous

Of course, if you’re a true hardcore personal scientists, you should consider using your own mass spectrometer to study your food contents. If you don’t have access to one, you can always try your own poor man’s equivalent: make your own spectrophotometer that uses the sensitive optical sensors in your iPhone to detect the light signatures given off by reflection off your food. Okay, maybe this will require some additional work on your part, but hey, isn’t that what personal science is?

Before you get too carried away, maybe read Gary Taubes’ Substack about how people die irrespective of which diet they follow. He mentions our late friend Seth Roberts in a list of seemingly health-conscious people who don't make it.

Then there’s my late friend, Seth, who succumbed to a fatal heart attack while we were hiking together in the Berkeley hills. I don’t think he was following my dietary precepts, but what if he was? I never got the chance to ask.

and

In the context of cancer, specifically, the influence of luck is “enormous,” as the renowned cancer epidemiologists Richard Peto and Richard Doll described it in 1981. “Even among genetically identical laboratory animals kept under conditions that are as closely uniform as possible, some will die of cancer in middle age, while others will live on into old age with no cancer,” they explained in what became the seminal analysis of cancer risk factors in a population. “Nature and nurture affect the probability that each individual will develop cancer, and luck then determines exactly which individuals will actually do so.”

Peto and Doll estimated that diet might be responsible for as much as 70 percent of all cancers (and as little as 10 percent) but after that, it was genetic predisposition and the roll of the dice that determined who and when.

Full text at (archive)

Canadian Economist Frances Wooley thinks it's odd that American Cancer Society recommends that colorectal cancer screening stop at age 75. Since life expectancy at that age is lower than the amount of time it takes the cancer to kill, they say, what's the point? Instead, Wooley argues, everyone over age 50, including those over 75, should get an at-home fecal immunochemical test (FIT) for colorectal cancer, rather than the more intrusive colonoscopy. If the FIT shows an anomaly, then fine, get a more detailed screening, but if not, bother.

About Personal Science

Professional scientists have fancy credentials and work on problems of interest to funding agencies, academic journals, or their principle investigator. But personal scientists work on whatever we want, in order to answer everyday questions or solve our own problems. We try to use the same scientific methods as professionals do, but we can explore issues they can’t, like highly personalized questions about health or our local environment, and we can often find answers more quickly. The key is to be open-minded, but skeptical.

Personal Science Week is published each Thursday. Paid subscribers can see our Unpopular Science series, where we share more controversial ideas that few professionals dare to touch, like some uncomfortable facts about plastic recycling.

If you have suggestions for new topics, please let us know.

Cronometer is probably the most comprehensive food app, especially for foods without barcodes. But their data is only as good as the databases they pull from.

Especially for natural foods like kombucha, it’s not surprising that nutritional values vary because manufacturing is not as standardized as ultra processed foods.

For example, I compared different reported amounts of B vitamins from various unfortified nutritional yeast brands. When I followed up with one of the companies, they gave me completely different testing results from their nutritional label. Different testing results from different batches…

Nutrition labels aren't one-size-fits-all: I like to check if a product contains palm oil, and compare how much added sugar there is per "serving". I know people who need to check if a product contains peanuts, or how much of the fat in a product is saturated fat.

I'm not going to restrict my diet to products that happen to have been tested by a 3rd party, but I would like to know which manufacturers tend to have accurate labels, and which don't. Ideally the FDA would enforce basic standards, but 3rd-party organizations like Consumer Reports could play a bigger role, too.

I'd redirect your criticism to simplistic labeling systems like Nutri-Score (which several countries have adopted). Who's to say chocolate can't be part of a healthy, balanced diet 😀