Professional scientists are taught to be careful with anecdotes, but for personal scientists that may be all we have.

This week: some anecdotes that turned out to be true.

Anecdotes are Usually Right

Jeff Bezos tells Lex Fridman a story about a time when the experts at Amazon claimed, based on tons of data, that customer service call wait times were minimal, only to watch in horror when Bezos himself called the number and was put on hold.

Jeff Bezos(01:34:00) By the way, a lot of our most powerful truths turn out to be hunches, they turn out to be based on anecdotes, they’re intuition based. And sometimes you don’t even have strong data, but you may know the person well enough to trust their judgment. You may feel yourself leaning in. It may resonate with a set of anecdotes you have, and then you may be able to say, “Something about that feels right. Let’s go collect some data on that. Let’s try to see if we can actually know whether it’s right. But for now, let’s not disregard it. It feels right.”

and

_when the data and the anecdotes disagree, the anecdotes are usually right. And it doesn’t mean you just slavishly go follow the anecdotes then. It means you go examine the data because it’s usually not that the data is being miscollected, it’s **usually that you’re not measuring the right thing.

Follow the Anecdotes

One of my favorite examples of how to follow an anecdote comes from A.J. Lumsdaine, a mother who was worried about her son’s eczema. Although she was a trained professional scientist, her first response wasn’t to conduct a clinical trial. She simply looked carefully at her n-of-1 family example. By carefully observing her situation, she solved her son’s eczema by systematically replacing detergent with soap. (Also see this well-done poster for a science conference)

Virologist Beata Halassy successfully treated her own cancer using an experimental method involving viruses she grew herself in her own lab. Her technique used two relatively mild and well-studied viruses to kick-start her immune system into fighting the tumor cells. Sure enough, the tumor shrank and detached itself in a way that made it easy to remove surgically, when she could prove that the immune system did the job. (Read the full account here)

A miracle! wonderful, right? This is what n-of-1 science is all about!

Not so fast. In her attempt to publish the good news, hoping others could benefit from her technique, she was greeted with a dozen rejections from academic journals. The problem? Ethics “experts” decided that it would be bad if some other cancer patient read this and decided to try it herself too. After all, an n-of-1 case like this is “just an anecdote” and some poor, innocent patient might use this as an excuse to avoid “real” treatments.

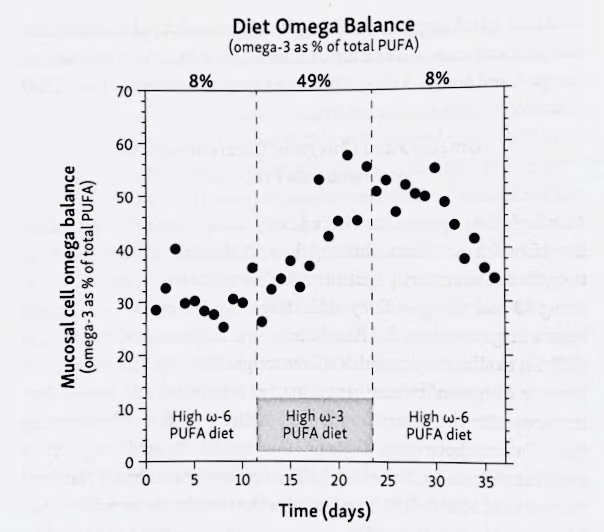

Many nutritionists recommend we eat more Omega-3 fats, like the kind found in fish oil. Scientist A.J. Hulbert agrees, but wanted to prove that it’s the ratio of Omega-3 to Omega-6 that matters. Rather than commission a fancy, expensive study, he did what a personal scientist would do: he tried it on himself. In his new book Omega Balance: Nutritional Power for a Happier, Healthier Life he self-experimented by deliberately cycling between diets with varying amounts of Omega-3 to Omega-6 ratios ("Omega balance"). He concluded that a high Omega-6 diet (seed oils) dramatically hurt his balance, while shifting back to a Omega-3 diet (salmon) repaired it.

Eric Jain has experimented with Omega-3 testing from Omegacheck ($66) for several years and concludes that his optimal amount is about 1/2 TBS of fish oil per day.

Don’t Trust All Anecdotes, Though

Perhaps the most famous n-of-1 experiment of all is the one that Barry Marshall reported in 1985, when he deliberately infected himself with Helicobacter pylori to prove that stomach ulcers are caused by bacteria, not stress-related overproduction of acid that mainstream science assumed at the time. Marshall later won the Nobel Prize for this discovery, and you probably know about it as an example of a lone iconoclast who boldly defied the expert consensus to single-handedly topple the Scientific Establishment™ with one daring act because nobody would approve a trial on human volunteers. Unfortunately the truth is less exciting: in fact most scientists had already concluded that ulcers were caused by microbes, but it was difficult to find a good treatment. Even Marshall’s original n-of-1 experiment ended up with mild symptoms that resolved on its own. The real reason for the myth? It probably has something to do with Barry Marshall’s disposition for self-promotion, helped by let’s face it, an inspirational David vs Goliath story that everyone loves. (Read a full, well-researched account of the history at Skeptical Inquirer 2004)

More Amateur Research

An undergraduate research team at Clemson University wondered: Is double-dipping a food safety problem or just a nasty habit? So they did the experiment and found:

We found about 1,000 more bacteria per milliliter of water when crackers were bitten before dipping than solutions where unbitten crackers were dipped.

The good news is that it depends on the type of dip. High acidic dips like salsa are much safer.

Columbia University Statistics Professor Andrew Gelman isn’t exactly an amateur, but he does like to do his own personal science research, like the time he weighed himself 46 times on a cheap bathroom scale. Each measurement was slightly different than the other, so he calculated the standard error (0.1 kg) but explains why that’s still not quite enough to be certain about his true weight.

And of course the inimitable Gwern used a similar technique to estimate, based on previous delivery times, the best time to check his mailbox. tldr; it’s complicated and depends on which mail carrier comes that day.

Lots more examples of scientists who treat themselves (2020)

And finally, Experimental Fat Loss is a site by an anonymous n-of-1 personal scientist who wants to lose weight. Although there are zillions of weight-loss ideas out there, this one is interesting for how he writes up his thought process, and how step-by-step he uses data to drive new ideas.

About Personal Science

This is your weekly summary, published each Thursday, of ideas and techniques that we think are helpful for anyone interested in adopting science for personal reasons. Don’t leave it all to the professionals!

Paid subscribers can access our Unpopular Science series, including this week’s summary of broad science and cultural news that most professionals likely will never hear.

If you have other questions or ideas, please let us know.