Personal Science Week - 241024 CBD

Does CBD really work? and finding new life in old data, plus the flu vaccine

Cannabidiol (CBD) is an active ingredient in cannabis (marijuana), derived from the hemp plant. Unlike THC, another chemical found in marijuana, CBD is not psychoactive. Thanks to the 2018 Farm Bill, it's legal in all 50 states and now found as an additive in thousands of products.

I tried CBD oil at various dosages over a period of a month to see if I can quantify its affects. Along the way, I discovered a way to find new results from old data.

Personal scientists are always on the lookout for safe, effective ways to optimize their health and wellbeing. One increasingly popular candidate is CBD (cannabidiol), a non-psychoactive compound derived from the cannabis plant. You’ve seen it advertised in health food stores, added to everything from chocolates to lotions, with claims of benefits ranging from pain relief to anxiety reduction.

Unlike its cousin THC (tetrahydrocannabinol), CBD won’t get you high or impair your cognitive functions. Instead, it interacts with the body’s endocannabinoid system, a complex network of receptors involved in regulating various physiological processes. Some studies suggest CBD may have anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and anxiolytic properties, though much of the research is still in its early stages. Given its potential to promote relaxation, I wondered if CBD might help improve my sleep quality.

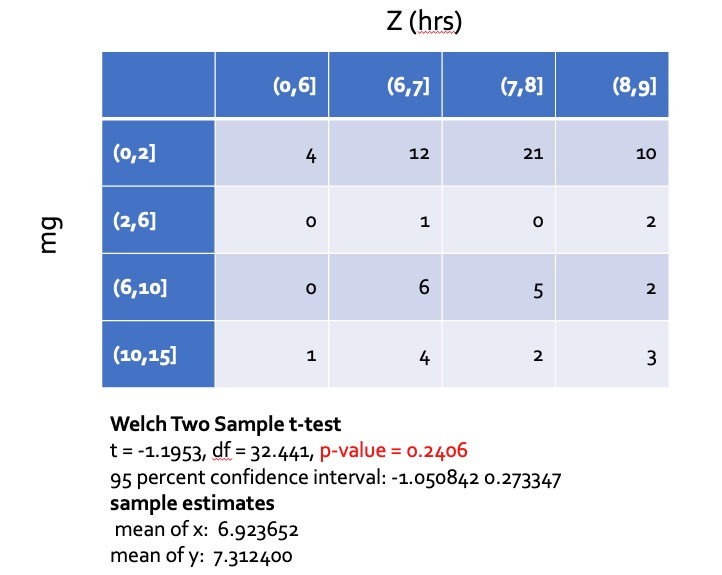

I conducted this experiment more than five years ago, when I did all the data analysis myself. Although I’m reasonable proficient at this sort of programming, setting up my code environment is enough effort that I only did the analysis once, on the data I had accumulated to that point: 27 nights with CBD and 47 nights without. I concluded that, while CBD seemed to help my sleep, the difference was too small to be significant (the p-value of 0.24 was well above the typical cutoff of 0.05). This is a table I presented to my local Quantified Self group at the time:

But now I have ChatGPT! Not only does this make the analysis far easier, but I can use a much larger data set, since I continued to track my habits even after the initial conclusions. In addition, I’m no longer limited by my inability to handle more complex statistics.

Plus, ChatGPT let me easily study the data from lots of different perspectives. I could ask, for example, to compare any analysis quarter-by-quarter (in case there are seasonal effects) or to limit just to dates when I was at home in my own bed. Although I couldn’t get the current ChatGPT to do add sunset-sunset times and other data automatically, it’s obvious that future versions of the LLM will easily enable that and similar features. It’s hard to overstate how simple it is to find real, interesting insights.

Results

After a long series of interactive data exploration with ChatGPT, here is the regression analysis for the entire year, limited to dates when I was home. The coefficient indicates the change (in hours) the predictor had on my sleep.

Conclusion: CBD doesn’t help my sleep.

For the full year, Coffee is the only statistically significant predictor, reducing my sleep duration by more than half an hour. Incidentally, the impact is dose dependent, which I know because my data tracks the number of cups per day. This seems to be a retrospective confirmation of what I suspected in PSWeek241010, that caffeine hurts my sleep duration even if it seems to not affect how quickly I fall asleep.

More Implications

I started my analysis hoping to revisit my old CBD discovery, but that turned out to be the least of my learnings. Yes, it was nice to reconfirm my old finding even if, sadly, I found no effect. But the real power is my ability to haul up old data sets. Without ChatGPT I might have spent a weekend or more trying to organize the data in order to do a useful analysis, and because of that I didn’t bother. But now my old data, collected in my case over decades, can find new life.

Personal science and the flu vaccine

The CDC says that this year’s flu vaccine is 34% effective (compared to last year’s 50%) against hospitalization for high risk groups. So if you’re in a high-risk group, by all means get a flu shot (and do all the other things you must do to optimize health, like maintain a healthy weight, etc.) But what about the rest of us?

The CDC bases its advice on a survey taken during flu season in South America (mostly Brazil), when hospitals tracked hospitalization rates among people in high-risk groups. Note that they did not track people who were not in high risk groups (i.e. the rest of us), or those who didn’t end up in hospital.

Think about how bad a flu would need to be before you or a member of your family goes to the hospital. These are very serious cases, almost always involving preexisting conditions, so it’s not clear that these people would have been hospitalized for other problems, regardless of flu.

The following chart from the widely-read public health influencer Your Local Epidemiologist is deceptive. The claimed reduction in “risk of going to the doctor” applies to high risk groups. Nobody knows the affect of flu shots on otherwise healthy people, but it’s almost certainly negligible.

Now you’re thinking, what’s the downside? If I’m otherwise healthy, even if the flu vaccine has a 1 in 1000 possibility of preventing a sniffle or two, the worst that can happen is a slightly sore arm. If your employer covers it and makes it easy, why not?

My answer is I don’t think there is a downside, but who knows. And would you hear about it if there were? Whatever bad side effects are almost certainly hard to detect, or we’d all know somebody who noticed a problem. And who’s going to fund or do the research? Certainly no mainstream hospital or university. I’m sure you can find conspiracy theorists who claim all sorts of things, and it’s fine for personal scientists to keep an open mind about all the possibilities, but ultimately we have to live in the real world and who has time to listen to crazies?

As we concluded last year:

The gold standard in evidence-based surveys, the Cochrane Review, concludes the shots work about as well as … um … that [statistically insignificant] p-value example above. Statistically you might prevent one case if you vaccinate 71 healthy adults, but you might also make them more susceptible to other illnesses. Check this 2019 Dutch study, which compared real flu shots to placebo among a thousand elderly people who were followed for twenty-five years (!). The shots made no difference in life expectancy.

Other Links of Interest

For more on public health, see Check Your Work by Katelyn Jetlina, a "Georgia Mom" who has been analyzing COVID data since 2020 after a career in IT. She does a deep dive in the counter statistics, including a conversation with Kelley Krohnert (The Local Epidemiologist, quoted above).

Unlike the last couple of years, unfortunately I didn't have time to attend the ISB Gut Microbiome Event Oct 16- 18 But everything you need to know is at (GitHub)

Richard Ngo on Why I am not a bayesian and instead why he thinks it's better to do model-based reasoning. He references what he calls "the critical debate in philosophy of science", about scientific realism and its "most defensible form" structural realism and concludes with this quote from Asimov: “Thinking that the Earth is flat is wrong. Thinking that the Earth is a sphere is wrong. But if you think that they’re equally wrong, you’re wronger than both of them put together.”

Peter Attia’s monthly Research Worth Sharing is usually a good place to find interesting news, but the October Research Worth Sharing isn't worth sharing. Just a bunch of studies that show exercise is good for you (who'd a thought?!)

Try this short Ideological Turing Test (I got 5/10, but I correctly identified Democrats 4/5 times and got only 1/5 Republicans).

About Personal Science

Be open-minded but skeptical. If you’re curious about the world, and you don’t necessarily want to rely on others for information about how to improve your health or performance, you might be a personal scientist. This is a weekly summary of ideas we hope will be useful to others who want to use science for personal, rather than professional reasons.

Paid Subscribers receive our Unpopular Science series, including this week’s post on the implications of AI and some rules for personal science. Even if you don’t want to become a paid subscriber, you may still want to check out the posts—most of the speculative stuff is ungated. If you’re interested in AI, you might also check the weekly discussion I write with The Wednesday Letter.

If you have other topics to discuss, let us know.

From everything I have read, CBN is the recommended sleep aid, not CBD. I do find 10 mg taken when I wake in the middle of the night is effective in helping me fall back asleep. I use a product by ECS therapeutics called Deep Sleep. No affiliation.

Perhaps CBD helps when you have trouble sleeping due to anxiety or overexcitement, but doesn't do much otherwise?

If we want to nitpick the vaccine one-pager: Isn't the 30-60% figure for reductions in *hospitalizations* of high risk patients, and not just for "going to the doctor"? For myself, what I'd want to know is how much the odds of getting sick enough to be able to pass on the virus is reduced!