Personal Science Week - 241010 Caffeine

Revisiting how coffee affects my sleep

Everyone knows that caffeine affects sleep in most people, but you’re not most people; you’re you, and personal scientists know there are always exceptions.

As a regular coffee drinker who never has trouble falling asleep, I thought I was an exception until recently an experiment with a new supplement made me reconsider.

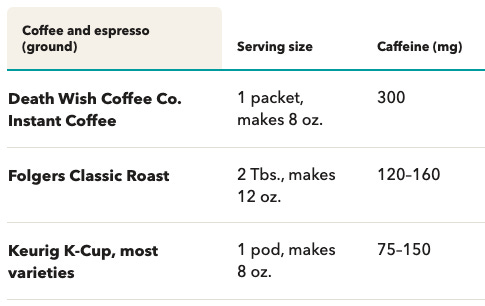

Back in PSWeek230622 I reviewed my coffee and caffeine consumption, with the surprise result that my drinking six cups per day was putting me well over the FDA’s “safe” limit on caffeine. The reason is straightforward: the “cup” on most home coffee makers is actually 5-6 oz, not the 8 oz that everyone else uses. I calculated my 6 cups/day (or 30 oz) like this:

One of my go-to brands of coffee is Peet’s Major Dickason’s Blend, which the manufacturer claims brews into about 133mg of caffeine in an 8-oz serving, or just under 17mg per ounce. Since my coffee maker’s “cup” is 5 oz, then each “cup” contains: 16.69 mg/oz * 5 oz = 83.45 mg of caffeine

When I brew and drink 6 “cups”, the total caffeine I’m ingesting would be:

83.45 mg/cup * 6 cups = 500.7 mg of caffeine, well over the FDA’s suggested maximum daily intake of 400mg

Although there’s a lot of variation in actual caffeine content, there’s just no disputing that my total caffeine consumption was pushing safe limits, so after that I dialed down to no more than 4 cups / day.

To be honest, I didn’t notice any difference.

I never have trouble falling asleep, no matter how much coffee I drink or when. I think it’s genetic: my grandmother used to prepare and drink an entire pot before bedtime because she found the warmth helped soothe her to sleep on cold Wisconsin nights.

But for the last few years, I have noticed a different sleep problem: I’ll often wake up in the middle of the night, wide awake and unable to fall asleep. Could that be related to coffee drinking?

The genetics of caffeine consumption has been well-studied. According to 23andme, I have the genotype C/C at rs4410490 and C/C at rs2472297. These are pretty common genotypes, found in between 66% of Asians and 85% of Europeans. It makes me an “intermediate metabolizer”, which means the coffee goes through me at a “normal” rate.

On average, caffeine has a half-life of about 5-6 hours for intermediate metabolizers like me, so let’s do the math on a typical day:

Morning Coffee (3 cups by noon, 285 mg total):

By 3:30 pm (3.5 hours after my last morning cup of coffee), I still have roughly half that caffeine in my system, or about 142.5 mg.

Starbucks Pumpkin Spice Latte (75 mg at 3:30 pm):

By 9:30 pm, 6 hours after consuming the latte, about 37.5 mg of caffeine from the latte would remain, and I’d still have some caffeine left over from my morning coffee too.

In fact I could easily have ~110-120 mg of caffeine (morning coffee + latte) still active in my system—the equivalent of a full cup right before bed.

Caffeine works mainly as an adenosine receptor antagonist—it blocks the natural “sleep pressure” that builds throughout the day. Could it be that, through years of coffee drinking, I’m tolerant enough that (like my grandmother) I fall asleep just fine, but that it affects the way my body stays asleep?

As I mentioned in PSWeek240502, I use a low overhead daily tracking method for most of my health-related activities: just a few brief notes stating in general the food I ate (“beef burger with bun”), which I can clean up later into a nice spreadsheet using ChatGPT. My Apple Watch tracks my sleep (including interruptions) and overall activity level. But unfortunately my simple notes don’t say much about coffee; since I drink my 3-4 cups every day, I only note the amount when, rarely, there’s a significant change. So it’s difficult for me to “rewind the tape” and uncover potential relationships between the timing of my coffee and the interruptions I have later in the night.

Meanwhile…

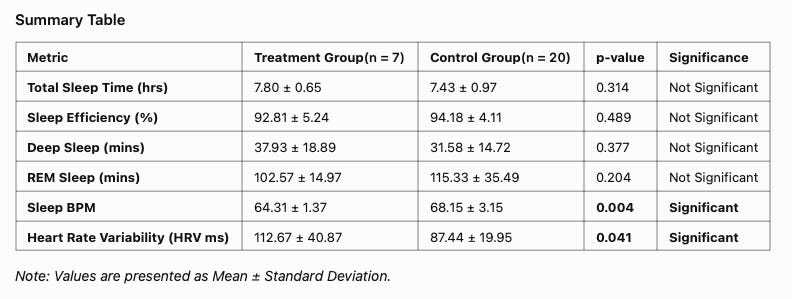

I recently received a sample bottle of a new sleep aid, Qualia Night™, which came highly recommended by attendees at the Biohacking event I attended last week (see PSWeek241003). These supplements contain a blend of various ingredients that supposedly “support” good sleep: Vitamin B6, Magnesium, Reishi mushroom extract, Hawthorn leaf, and many more. Notably, they do not include melatonin, which the company says your body will generate naturally from the other ingredients.

But does it help my sleep? So far, after 7 nights my rough conclusion is that any differences are pretty minor—certainly not enough to justify the $70/month retail price.

But, this doesn’t take into account my caffeine consumption. Anecdotally, I felt great on several—but not all—of the mornings after taking the supplements. On at least one of the exceptions, I’d had coffee in the afternoon. What will happen if I stop all caffeine?

I’ll run that experiment and let you know in a future post.

More Caffeine and Coffee Links

In case you’re wondering, a lethal dose of caffeine is about 10 grams or 150mg / kilogram of body weight. That’s more than 20 times the most I’ve ever had in a day.

Alex Chernavsky did his own experiments and found that coffee clearly increases his reaction time.

Center for Science in the Public Interest has compiled a chart of caffeine levels of common commercially-available products

But if you have some ethyl acetate (aka nail polish remover) and a few other high school lab type supplies, read these instructions for how to measure it yourself.

About Personal Science

Be open-minded, be skeptical: those are some of the tenets to remember if you want to use science in your personal life. We publish ideas and thoughts each Thursday, but if you have more topics you’d like to discuss, let us know.