You’ve probably heard that it’s healthy to drink 8 glasses of water a day. Although that advice is almost certainly a myth, it seems to me that the quality of your water is just as important as the quantity. But how can you tell if the water you’re drinking is good for you?

Water testing databases

All municipal-run water systems are required to undergo regular testing, and those results are usually posted publicly. Look at your city’s web site, or watch for that occasional email or mail that they send you for details.

In addition, numerous other organization, public and private, also test drinking water. The Environment Working Group, based in Washington DC, is a non-profit organization that promotes numerous environmental issues including safe drinking water. EWG’s Tap Water Database is a national database, sorted by Zip code, that lets you look up all the latest test results for your neighborhood.

Conveniently, besides the minimum water standards required by the government, EWG data includes results for contaminants that aren’t currently regulated. You can decide for yourself whether you think these levels are acceptable, and the site gives specific recommendations for filters that can remove any bad stuff it finds.

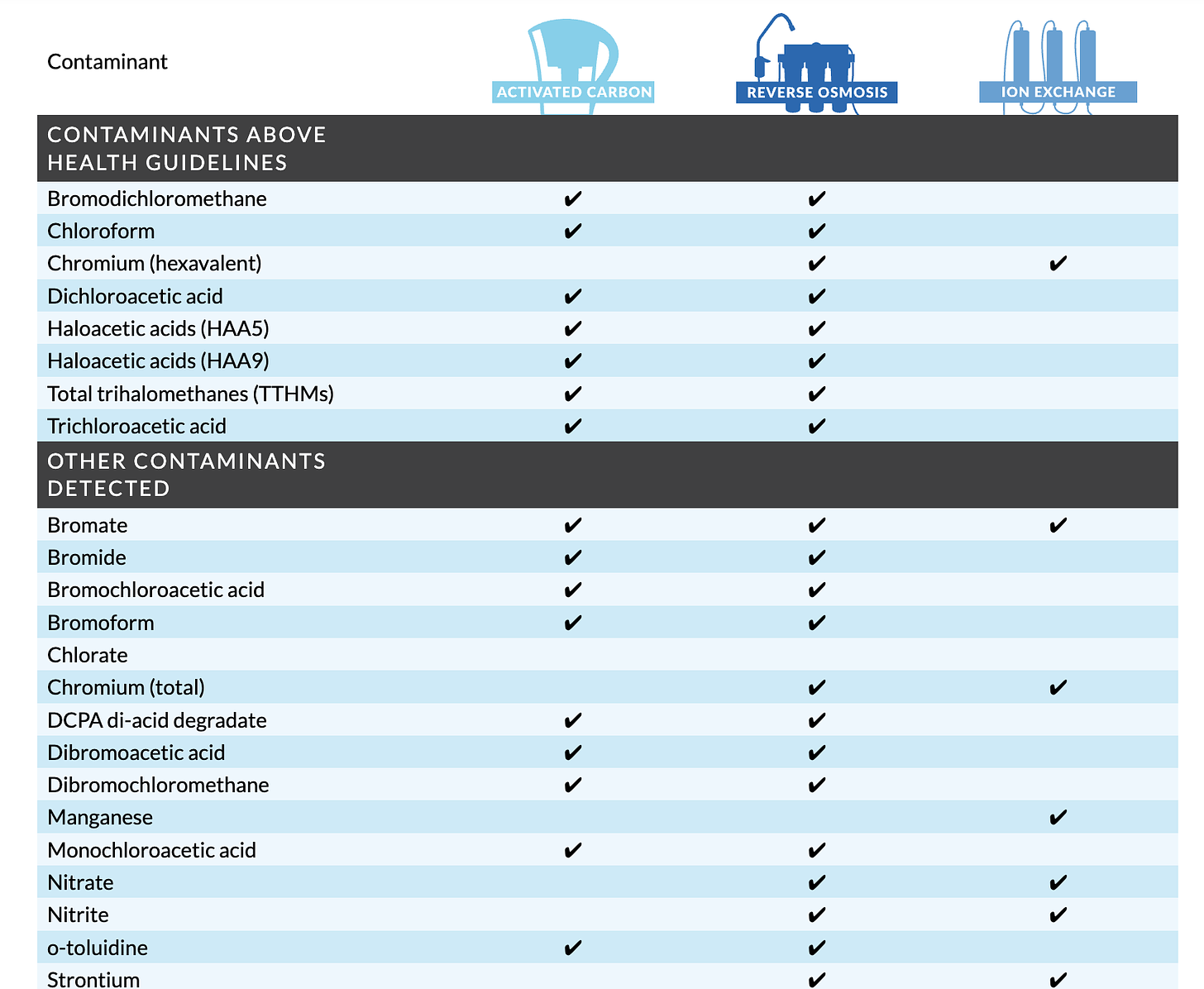

For example, here’s a partial list for my home town of Mercer Island, Washington:

Are these levels dangerous? I don’t know, and — as a personal scientist skeptical of everything, including tables like this one — I wonder too if those “contaminants detected” or “potential effect” results are correct anyway. Still, armed with this information I have a path to make up my own mind.

Test your drinking water

Regardless of what you think of the accuracy, what gets tested by the city utility and what makes its way through pipes to your house may be completely different, so the best way to find out about contaminants is to test for yourself.

You can buy home water testing kits for under $25 or so on Amazon. I don’t have a particular recommendation; I bought one from a random vendor but I bet they’re all about the same.

These kits typically come with special test trips, usually in quantities of 20 or more, that let you sample multiple times. You dip the strip in your tap water and watch for any color changes. In addition, the fancier kits contain special vials of additional chemicals. Drop some of your tap water into the tube and look for color changes.

I brought my kit with me on a trip to Beijing, where I wanted to see if the tap water was safe to drink.

First I tested pH. The results, 8.0, means the water is fairly alkaline. Since the human body keeps blood at a range of 7.35 to 7.45, some people (including the long-time Singularity champion Ray Kurzweil) think high-alkaline water is good for you. In fact, some health nuts buy expensive machines ($1000+) so they can drink it all the time. Anyway, the point here is that probably the pH levels in this tap water aren’t bad.

The water is slightly hard: between 100 and 200 total calcium plus magnesium. This is obvious from taking a shower: it feels like the shampoo won’t come out of your hair, and it’s not easy to get a good lather going with a bar of soap. But, at least according to the World Health Organization, this doesn’t seem to have an effect on health.

Another test, for Chemical Oxygen Demand, doesn’t check for any chemicals per se, but just the level at which oxygen is absorbed in the water, considered a proxy for the amount of organic compounds (i.e. living things). The closer you can get to zero the better, but my level is under 5 and considered fine. To give you some perspective, Switzerland apparently has a law prohibiting the dumping of water that is over 200.

I also tested nitrate ion concentration, which is associated with sewage and/or fertilizer. Ideally, this would be zero, but mine tests at just under 0.5 parts per million (ppm). The US Environmental Protection Agency sets the limit at 1 ppm, so it looks okay, though of course I wish the number were lower.

There are many more tests I could conduct, but so far my bottom line is that the water on my trip is safe. Sure enough, I appear to be just fine after drinking it.

This test is easy enough and cheap enough that it’s worthwhile to bring on your own travels. It’s also nice to try once or twice just for fun and as a simple way to reassure that the numbers I get from my city are roughly correct.

We wrote about fluoride in PS Week 230504, which you may want to check out if you’re having unexplained health issues.

More links worth your time

Join me at the Biohacking Conference in Dallas May 29-June 1st. I’ll be showing off my new retinal age camera and much more.

Nat Friedman, former CEO of GitHub and the driver behind that effort to read ancient books buried by the Vesuvius - Pompei volcano, wants to find out exactly how much plastic chemicals are in our food, drinks, and household items. Nominate items to test at https://www.plasticlist.org/

Elizabeth (AcesoUnderGlass) reviews nitric oxide nasal spray / “Enovid”, a promising treatment for respiratory infections like colds and COVID. You spray the nitric oxide in your nasal passages, and it kills the viruses. She concludes that it might be useful in temporary, high-risk situations, but that you probably don’t want to use it routinely. (via Astral Codex)

We’ve written about AI many times here in PS Week, and if you’re interested in more then please check out a new project I’m doing with my long-time Wharton School classmate, Sami Karam: we’re having a weekly conversation about the impact of AI on investing, which you’re welcome to join by subscribing to Sami’s excellent Substack The Wednesday Letter.

About Personal Science

Early Renaissance thinkers often used the Latin motto Ad Fontes—meaning “to the sources”—to describe their approach to knowledge: prioritize original texts over hearsay or commentary to uncover the truth. This led to an interest in languages, especially ancient Greek and Hebrew, but also to an insistence on raw data collection from newly-invented telescopes, or from new procedures like dissection.

Personal science brings that same philosophy to everyday life. Don’t trust something just because you read it somewhere, or because an expert says so. Wherever possible, think about it and apply it to your own situation — Ad Fontes.

This weekly newsletter is free, but paid subscribers can access our extra posts on Unpopular Science, for topics of personal interest that are too controversial to distribute widely, such as our post about developing immunity to snakebite.

If you have questions or suggestions for future topics, let us know or leave a comment.