Personal Science Week - 240502 AI Self-Tracking

Easy self-tracking made more useful with ChatGPT

Personal science often involves data collection (“self-tracking”), sometimes to such ridiculous levels that people forget the point of it all. But simpler, goal-oriented tracking is almost always best.

This week we’ll look through an example of how I’m using generative AI (genAI, aka ChatGPT) to find quantitative patterns in simple text notes.

The Best Is the Enemy of the Good

I used to keep a lengthy spreadsheet where I carefully tracked all my food, sleep times, and more. Some of that can be automated — for example, my Apple Watch knows about sleep and exercise — but it’s a hassle to keep it up-to-date and in the right format.

Plus, over the years I’ve learned that I rarely use that carefully-collected data for anything useful. Who cares how much of this-or-that food I eat, unless I’m trying to rigorously follow a new diet?

But tracking some information is useful. For example, I’ve noticed that some mornings for no particular reason I’ll wake up with a very mild headache that seems to disappear within an hour or two. This happens infrequently enough, and is mild enough that it’s not worth it for me to go all-in quantified self and laboriously record every last thing I did in hopes of finding the trigger.

Instead, for the past few years I’ve simply kept a running text file with very rough notes about what I did that day. If I miss a day, or forget to track something — no big deal. But on those rare mornings with headaches, I’ll make a special effort to write as many details as possible. Then, I just search for ‘headache’ to see if I can recognize any patterns from the previous episodes.

That’s a simple system that requires far less effort than some of the alternatives. But the best would be if somehow I could combine the simplicity of my basic notes with the power of a spreadsheet or structured database. Then I can make all the fancy calculations about average hours of sleep per night, correlation statistics, and more.

This is a great project for ChatGPT.

My Simple Notes

My daily notes are pretty basic. I just enter a few lines each morning in one big text notepad (I make a new file each year). I write in reverse order, so the latest day is on top. For example, here’s a snippet from two days worth of notes:

Fortunately ChatGPT and other genAI LLMs make it surprisingly easy to convert my crude notes into a usable spreadsheet like this one:

and after that I can run all the quantitative statistics I can imagine.

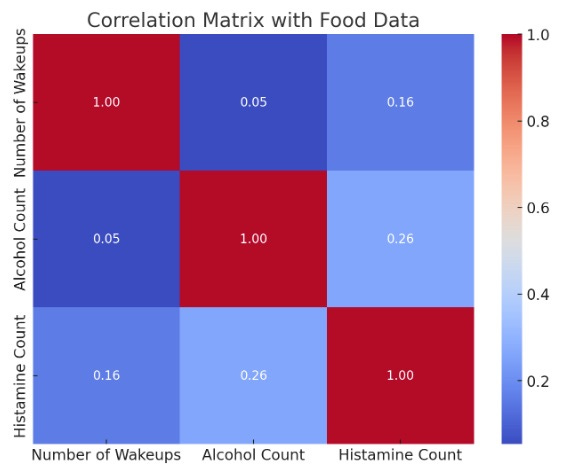

ChatGPT can help me with that too. I gave it my new spreadsheet in hopes of uncovering potential reasons for my middle-of-the-night wake-ups, and it generated this heatmap:

Blue colors show low correlation, so in this case it didn’t find any particular relationship. But no correlation is itself interesting because now I know to de-prioritize looking for food-related patterns associated with nightly wake-ups.

Note how ChatGPT automatically classified all my food items: it lumped together words “beer” or “wine” under “alcohol”; any food with high histamines (e.g. fermented foods, aged cheese, etc.) was similarly combined into one category.

But what about the headaches? When I ran my spreadsheet through Google Gemini, it suggested:

High-Fat Foods: Several instances involve the consumption of high-fat foods like cheese, pizza, bacon, and red meat the day before a headache. While healthy fats are important, excessive intake might contribute to headaches in some individuals.

Processed Foods: Processed meats, snacks like tortilla chips, and sugary treats like apple pie appear on some headache-preceding days. These foods can contain additives and preservatives that may trigger headaches in sensitive individuals. Alcohol: Alcohol is a known trigger for headaches and is mentioned before two headache instances.

I don’t have enough data points yet to really say I’ve found a correlation, but these are some great ideas I hadn’t previously considered. Often with personal science, that’s the real goal anyway.

If you’re interested in trying this for yourself, you can find more details including the specific prompts, at https://ai.personalscience.com/.

More Personal Science News

Sean Gibbons, from the Institute for Systems Biology, delivered an update last week about some interesting new microbiome science that will have implications for personal scientists. (You can watch the 1-hour replay on YouTube). His lab’s new Metagenomic Estimation of Dietary Intake (MEDI) promises to give an accurate assessment of a person’s diet through a gut sample – much better than an easy-to-forget questionnaire. And they showed “My Digital Gut”, a product they want to build that will let consumers simulate the effects of various diet changes, based on a gut sample.

Our friend Mike Sinn has been working on an ambitious project called FDAi, an open-source “set of tools and framework to create autonomous agents to help regulatory agencies quantify the effects of millions of factors like foods, drugs, and supplements affect human health and happiness.”

Also see their ambitious plans for a Clinipedia of all available data on the effects of every food, drug, supplement, and medical intervention on human health. See more at fdai.earth

Adam Mastroianni’s Experimental History is always interesting, but this week’s post is especially worth reading for its links to a (successful) replication of that “soup bowl experiment” (where people eat more when a soup bowl is automatically refilled), why you can’t trust Amazon Turk-generated research anymore, and much more.

About Personal Science

Personal Science is the process of using the scientific method to solve problems and get better results on an individual, personal level. Following the motto of the Royal Society, established in 1660, nullius in verba, we take nobody’s word for it.

This newsletter is a weekly summary of a few observations we think will be interesting to anyone who wants to be a personal scientist. Our weekly post is free and public, but we also have a separate post for paid subscribers who can be trusted with information that is too controversial for wide circulation, such as our latest summary of the case against the virus theory of disease.

If you have questions or suggestions for future topics, let us know or leave a comment.