While heavy reading isn’t exactly required if you want to be a personal scientist, it turns out that most of us read a lot.

This week we discuss some ideas for tracking and improving our reading experience.

Only 53% of respondents to an Economist/YouGov poll said they read a book in the past year. Of those who did, the average was 11 books. (Read the whole survey, including a way to compare your reading volume to others)

These averages are an interesting starting point, but hardly the whole story. As a representative sample of Americans, this poll feels about right — we all have friends and family who basically never read books. But even if you’re a voracious reader, you’ll never read even a fraction of the 750,000 new ones published each year, much less the 140 Million books that have been published in history. Simple math: even if you read 100 books per year for 50 years — a virtually impossible stretch goal — that’s a mere 5,000 — fewer than the number stocked in a typical independent bookstore.

So if you’re going to read, might as well be selective. That same Economist article did the math using the popular 1,000 Books to Read Before You Die by the book critic James Mustich. If you read 30 minutes a day, it would take you about 50 years to get through them

What would it take to be more deliberate in the books we read?

Track your books

First of all, you’ll need a way to keep score. In the old days, some of us would keep a notebook or a spreadsheet whenever we finished a book. Now it’s easier to just use Goodreads.

Amazon bought multiple book-tracking sites a decade ago and dropped the others in favor of this one. It has all the features you’d want: search for titles, view and write reviews, publish (or not) your books to friends, find communities organized around specific book times.

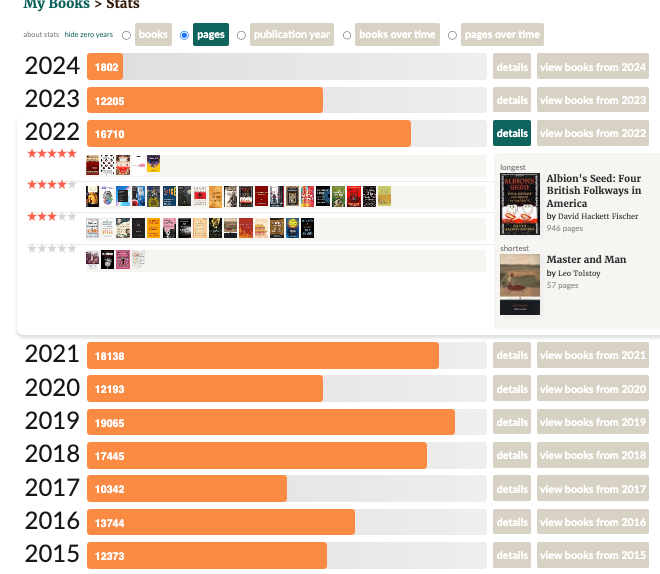

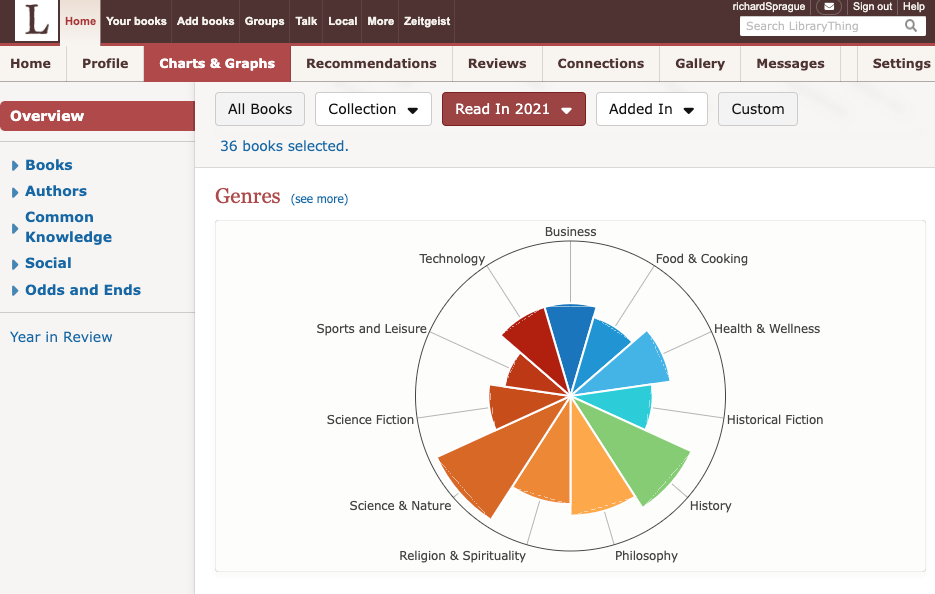

Once you’ve entered your books, the site allows some rudimentary graphic views to help you visualize how much you’ve been reading across time.

The most important feature for tracking is the ability to export your full library, with all its metadata, to a CSV file. For personal scientists, this the bare minimum requirement if you decide to adopt any long-term tracking software. A big company like Amazon can shut down the site or make major changes at any time. Don’t risk becoming dependent on one company. As long as you can download your lists, you’re safe.

But Goodreads has plenty of problems besides the “lock in” you’ll feel with the dependency on one company for so much of your reading life. The site is slow, especially on mobile. The company seems to invest very little in improving the site with new features or a better interface.

The alternative booktracking site, LibraryThing, is better on most features. They even let you upload your Goodreads library, so you won’t miss a thing if you switch. You can do much better plots and study your library in more detail than with Goodreads.

I tried the switch, and was happy I did, but ultimately came back to Goodreads because too many of my friends are there. It’s easy to move your library back and forth, and probably I’ll go to LibraryThing for good someday if I can convince more friends to change. (Friend me on Goodreads or LibraryThing and we can compare).

Measure your reading speed

Before starting a new book, you can estimate how many hours it’ll take to complete it with howlongtoread.com.

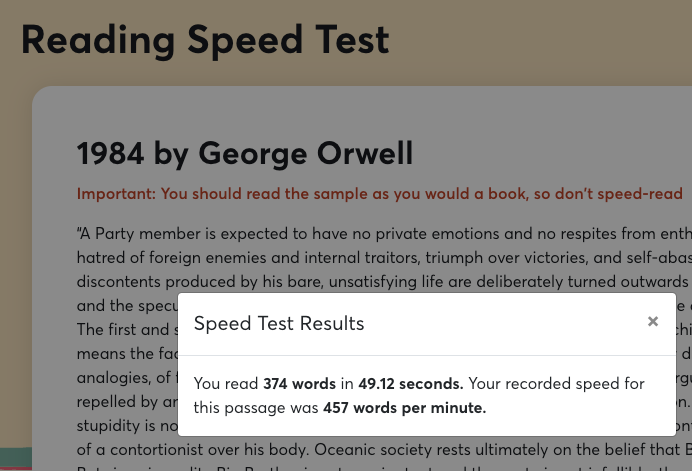

Tim Ferriss offers his tips for how to improve your reading speed, but you may find more down-to-earth examples on The Quantified Self site. Kyrill Potapov, for example, describes how he found his optimum reading speed. Most speed-reading involves practice at keeping your eyes from backtracking—the most common form of inefficiency while reading. You can get apps that force you to read one word at a time, in a linear sequence that, with practice, can get you reading much faster. I used Spritz to get my reading speed up to 1000 rpm — with a little practice it’s not that hard.

We won’t go into more details in this post. If you’re interested, there’s plenty of advice out there if you want to improve your reading speed. Let us know in the comments if you have something in particular that you like.

About Personal Science

Until the term “scientist” was invented in the 1830s, people who took a systematic approach to understand the world were called philosophers. Natural philosophers were those, like Isaac Newton, who specifically applied themselves to understanding the physical world around us. Now that we have the word “scientist”, what do you call a philosophy that tries to apply rational thinking to every part of daily life? We call it Personal Science, and this newsletter tries to be a brief, weekly summary of the consequences of that approach, hopefully in a way that will be interesting to others who are just as curious as we are.

For interactive discussions with other Personal Science-minded people (including me), please join the Open Humans Weekly Self-Research Call, every Thursday at 10am Pacific Time. Open to everyone, and very friendly. (See Personal Science Week - 15 Sep 2022).

Addendum

The vast reading riches of the internet has made it all the more frustrating for me to enter a library or bookstore these days: so many wonderful books, so little time! And with services like Kindle Unlimited, not to mention audiobooks, the biggest problem for serious readers is how to take advantage of all those books you (want to) read.

In PS Week 230330 we gave our tips about free resources for books and academic papers, and we also warned about the “collector’s fallacy” — don’t fool yourself into thinking that you really learned something just because you “read” it. You must take note-taking seriously, as we wrote in PS Week 230302.

That said, here are a couple of additional reading-related resources to consider.

Calibre: eBook Library Aggregator

I rarely use print books anymore. I read almost everything on my Kindle. But once you have hundreds, or even thousands of ebooks, Kindle alone becomes unwieldy. The solution is