Personal Science Week - 240125 LMHR

Cholesterol and Lean Mass Hyper Responders

My cholesterol levels go through the roof on a ketogenic diet, and I’m not alone.

This week we describe Lean Mass Hyper Responders (LMHR) and its implications for the rest of us.

My cholesterol

My blood cholesterol has been high for as long as I’ve been testing. I can control my levels with statin drugs, but is it a good idea to take such a powerful drug indefinitely unless I know what other effects it has on me?

My cholesterol levels go even higher when I’m on a low-carb, ketogenic diet, even for a few days.

So is Keto bad for me? Should I do more about my high cholesterol?

Lean Mass Hyper Responders

David Feldman is a personal scientist who, through various crowd-sourced experiments, came up with an explanation that seems to describe me. When he noticed that his cholesterol levels appear to soar on a ketogenic diet, he proposed a new body type, Lean Mass Hyper Responders (LMHR), to describe people who meet the following requirements:

LDL of 200 mg/dL (5.17 mmol/L) or higher

HDL of 80 mg/dL (2.07 mmol/L) or higher

Triglycerides of 70 mg/dL (0.79 mmol/L) or lower

After crowdsourcing a large enough sample of people who followed his protocol, he published his proposed LMHR idea in a standard peer-reviewed medical journal. This week, his collaborator Nicholas Norwitz went a step further with another publication showing that Oreos lower cholesterol more than statins.

Now obviously, this experiment wasn’t seriously proposing that anyone eat Oreos to lower their cholesterol. The intent was to be provocative and get attention for the LMHR thesis. But as a personal science experiment, it’s perfect because it shows how you a normal person can make an interesting scientific claim, backed with good data in support of a hypothesis that deserves further study.

See Personal Science Week - 14 July 2022 for my experience with a special powder that can bring you into ketosis without the diet.

Testing your cholesterol

Azure Grant and others at Quantified Labs did a cholesterol experiment that we discussed in PS Week 231109 where several personal scientists showed how cholesterol levels change significantly throughout the day.

We’ve been fans of the SiPhox at-home blood testing system (see our original discussion in PS Week 17 Nov 2022). They’ll test your LDL, HDL and total cholesterol, as well as other important lipids including APOB, for about $95.

David Feldman also operates the non-profit Own Your Labs , which sells very low cost blood tests through LabCorp. They’ll let you test your cholesterol at your local LabCorp for $8.75.

Links worth your time

Netherlands-based Radboud University offers a 5-day Introduction to the Theory and Practice of Personal Science. The online course costs $500 and is taught by several experts including the authors of the book “Personal Science” (read our review)

Another class to consider: Understanding Medical Research: Your Facebook Friend is Wrong, free on Coursera. It’s taught by Perry Wilson, from the Yale School of Medicine (and author of the excellent MethodsMan blog)

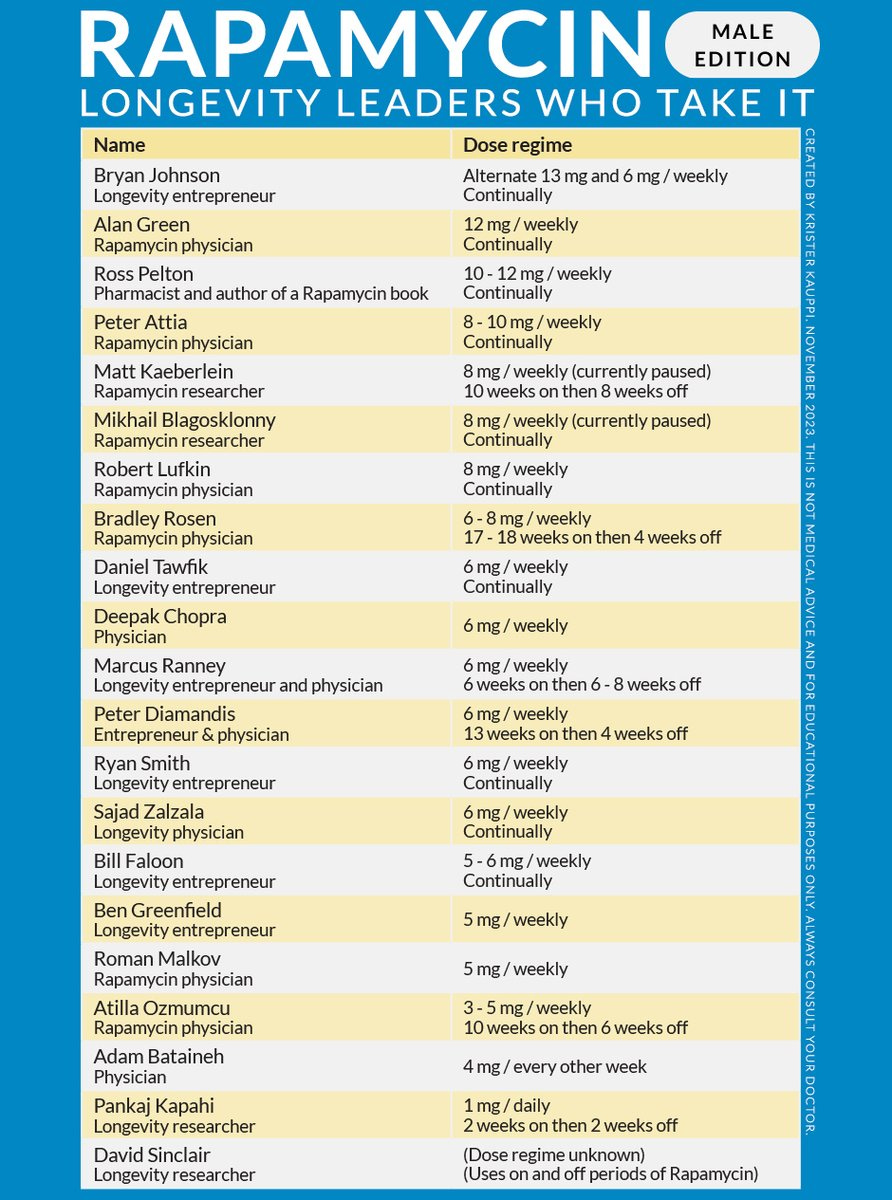

Krister Kauppi (@KristerKauppi) wants more people to trial rapamycin for its effect on slowing or reversing aging. If you live in Seattle and are over age 50, you can join a a rapamycin clinical trial that’s hoping to evaluate its effectiveness in treating periodontal disease.

Pretty much every artificial sweetener was discovered accidentally, despite huge research attempts to find them more systematically. Is serendipity under-rated?

Yes, double-dipping really does spread more germs, according to an undergraduate science experiment from 2009.

About Personal Science

How do you know for sure? In a complex world with competing and often contradictory information, Personal Scientists believe that everyone can apply the techniques of science to edge closer to the truth. It’s not easy. Even if you want to simply “trust the experts”, you must choose which experts to trust.

We try to encourage Personal Science through these weekly updates, but most of our posts are on topics that are mostly timeless, so check out our archives for more information. Paid subscribers can read our Unpopular Science series, with topics that are too controversial to unload on the general public, such as our recent one on Data Science.

As always, please let us know if you have other topics you’d like us to discuss.

Your high total cholesterol and LDL-C numbers are fascinating, particularly since I tend to think you have better genes overall than I do. Most of the contributors in "Cholesterol Clarity," Moore and Westman, 2013, comprising about 30 people, would tend to say you may be worrying too much, and that a consideration of LDL-P might be beneficial in more accurately characterizing your genuine risk, this idea of Pattern A (Normal, Good) vs Pattern B (Abnormal, Bad). What that is all about is the relative size and nature of the LDL particle, and there is a fairly large amount of evidence that this is a key factor in determining whether someone actually develops heart disease, not their LDL-C assay.

There is considerable info on interpreting LDL-P results in the book, which to be done accurately, requires an analytical technique such as gel electrophoresis. However, there is also the "poor man's" technique of simply dividing triglycerides by HDL, where a ratio of < 2.0 is good, connoting a tendency towards Pattern A, and a ratio of >3.5 is less good, indicating a greater likelihood of Pattern B.

I last had my lipids checked in July 2023, and they were

Total Cholesterol = 227 mg/dL

HDL-C = 139 mg/dL

LDL-C (Calculated) = 81 mg/dL

Triglycerides = 36 mg/dL

My ratio calculates as 36 mg/dL/139 mg/dL = 0.26, which is extraordinarily good. If I were to actually have LDL-P determined via gel electrophoresis or another analytical technique, there's not much doubt my LDL particles are going to come back as Pattern A, the normal, good kind.

Volek and Phinney in "The Art and Science of Low Carbohydrate Living," 2011, touch on this issue of LDL-C typically being a calculated value. The equation generally used for doing do was developed by William Friedewald and colleagues in 1972, and a major assumption in its use is that the ratio of triglycerides to cholesterol is constant. There is some amount of evidence that the equation develops linearity problems at both high and low triglyceride levels. My calculated LDL-C value of 81 mg/dL is already low and benign, but the actual value is probably even lower than that.

You can apparently tolerate statins well, which is great, and they do have benefits. But I happen to be someone who had two uncles who both died of an ALS-like condition they developed after being prescribed statin drugs, and I have a book by Dr. Duane Graveline "The Dark Side of Statins," 2017, where he relates a similar issue. Assuming statins were involved in precipitating the condition, the most likely mechanism is their fundamental interference in the mevalonate pathway, of which dolichols are one of the products (the cholesterol molecule is another).

Dolichols are molecules, that among other things, supervise repairs in DNA, of which a person requires on the order of tens of thousands per day. The model developed in regard to these ALS-like conditions are mitochondrial DNA mutations in neurons not being immediately addressed due to a shortage of dolichols, the errors then becoming embedded, and unfortunately, this can be permanent. The errors eventually contribute to malfunctioning in the associated mitochondria, and if enough mitochondria are impaired, this can negatively impact the functioning of the neuron overall. I suppose the neuron could even die in some cases, but the impairment of neuronal functioning is potentially bad enough simply by itself.

Now, all three of these people, my two uncles and Dr. Graveline, unquestionably suffered from heart disease, and their lives may have been extended by their use of statins. To his immense credit, despite being motivated to go to the effort of writing more than one negative book about statin drugs, Dr. Graveline indicates they do save lives, through at least four separate possible mechanisms. However, what many in the medical establishment don't seem to realize is that it's their inherent anti-inflammatory properties that probably really matter.

Graveline relates that when they were first developed, statins were characterized as "super aspirin," an appellation rejected by the pharma community as insufficiently glamorous. However, they actually do approximately what aspirin does in regard to heart disease and are simply a great deal more powerful. They are beneficial and extend life in many cases, but their potential drawbacks also need to be considered.