Personal Science Week - 240111 Plasmalogens

Testing the ProdromeScan™ and the links to Alzheimers

Dayan Goodenowe is a neuroscientist who spent the past twenty years perfecting a type of mass spectrometry that has implications for diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimers dementia.

This week I’ll summarize what I learned after I took Dr. Goodenowe’s latest blood test.

The name of Goodenowe’s company, Prodrome Science, is a clever reminder that these tests are intended to provide a prodrome — an early hint that something’s about to hit, like the prodrome that migraine sufferers get an hour or two before symptoms.

The ProdromeScan test, which costs about $500, requires a blood draw at an approved facility. You can also book a home blood draw with a phlebomist from Travalab. I did mine at the offices of Kevin Perrott, CEO of OpenCures, who also walked me through the results.

Like most comprehensive blood draws, you really should do this on an empty stomach but I unfortunately had just finished a Panera egg sandwich just before mine. Although that won’t affect most of the readings, it’s an important caveat when I compare my results over time. (See our lengthy discussion of the problem of blood test variability in PS Week 231109)

Plasmalogens and Alzheimers

If you have a basic layman’s knowledge of the subject, you probably associate the word “cholesterol” with something bad, but in fact cholesterol is among the most important chemicals in your body. It makes up 30% of all cell membranes, and is especially important for your brain, which holds about 1/4 of your body’s cholesterol.

Goodenowe writes about this in gory detail in his book Breaking Alzheimers, which I found to be a useful, though tediously technical, review of the role that cholesterol plays in Alzheimers dementia. The tldr; is that your neurons rely on a type of lipid called a plasmalogen, to maintain their cell membranes and facilitate the proper activity your brain needs to function.

You’ve probably heard about APOE-4, the “Alzheimer’s gene” (Your 23andme results will show whether you have it or not). Although only something like 25% of us have that variant, about 80% of people with Alzheimers do. Importantly, even if you don’t have that variant, you’re not off the hook: 20% of Alzheimer’s patients pass the gene test.

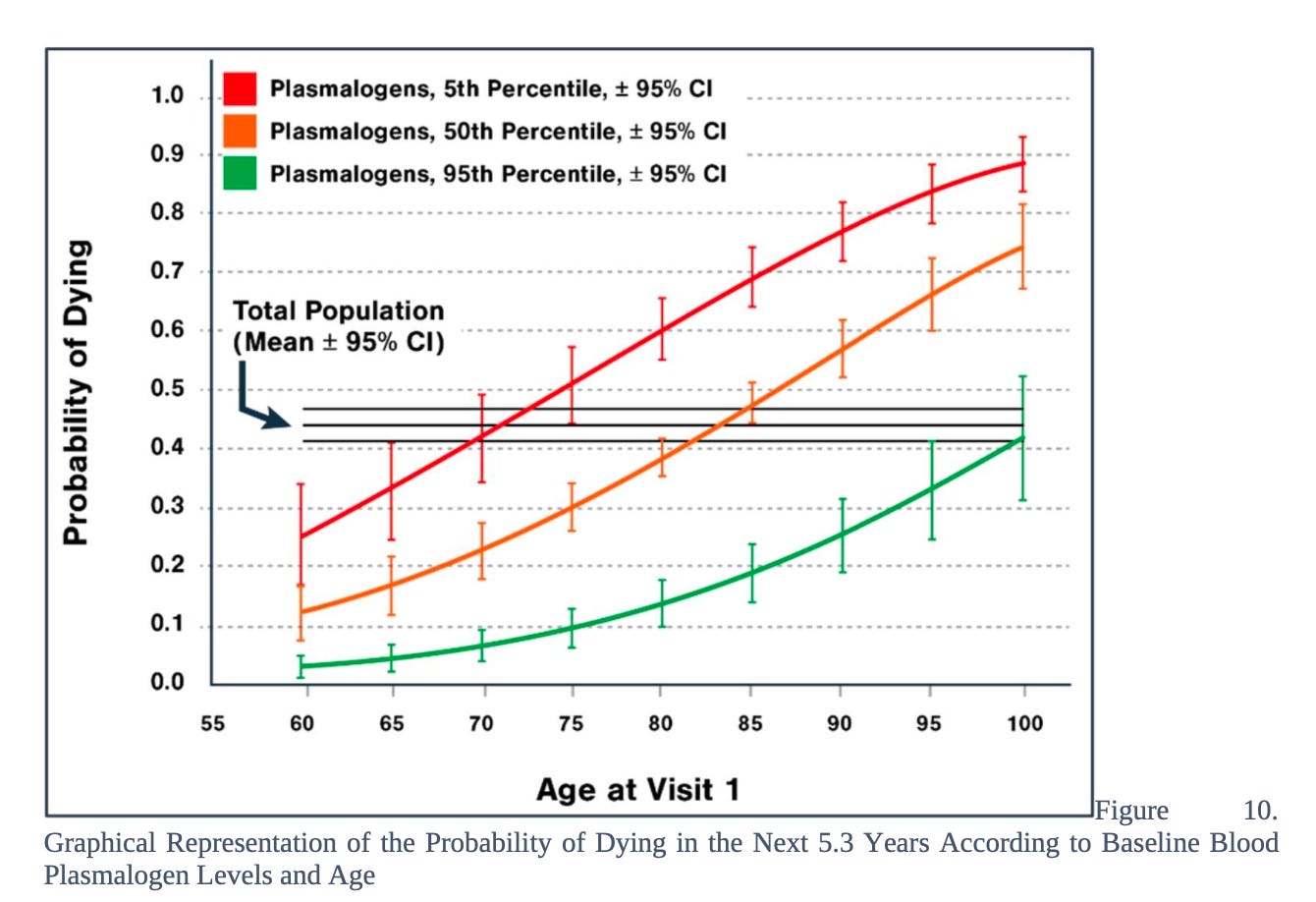

Goodenowe claims the missing factor is plasmalogen, and he shows based on a 1200-person longitudinal study, that people whose levels were sufficiently high were very unlikely to get Alzheimers — and vice versa — regardless of APOE status.

I’m simplifying the conclusion — and the FDA restricts the wording of what can legally be claimed — but the net result is that the ProdromeScan test, by determining your levels of blood plasmalogens, might be a good proxy for dementia risk.

My ProdromeScan™ Results

So how did I do?

Unfortunately, I found the ProdromeScan terribly difficult to decipher. Mostly I care about whether I am at risk for Alzheimers, but the test doesn’t explicitly say that one way or another, perhaps due to the FDA limitations just noted. Instead it gives a technical summary of the percentile results for each blood factor, alone with a “Z-Score” that indicates how far I differ from the thousands of others who’ve been tested.

Generally speaking, my Z-Scores were high and indicate that I’m at low risk of Alzheimers (incidentally, that matches my APOE-4 negative status).

Goodenow’s book includes what he calls “the scariest graph I’ve ever created” to show the very high risk of dying if you have low blood plasmalogens. Fortunately, according to this chart and my results, my odds are pretty low.

But if your results are worse than mine, Goodenow’s company claims to have perfected a series of supplements supposedly proven to increase your plasmalogen levels for about $100 for a month’s supply.

I have no idea whether this works or not, but if my plasmalogen levels were low I’d take this seriously.

References and Recommendations

I first learned about plasmalogens from Dr. Adam Rinde’s One Thing podcast, which along with his Sound Bites Substack I recommend for its range of open-minded, under-reported ideas about health and wellness. Dr. Rinde says the supplements have helped his own focus and cognition and points to a randomized controlled trial from Japan that appears to show benefits.

About Personal Science

I’m not a doctor. I have no formal medical training of any kind. Please don’t rely on me for health advice. But who should you rely on, and why would you trust them more? That’s the central question we ask in this newsletter and our answer is: don’t trust anyone. Be skeptical. Nobody cares more than you do, so learn to do your own observations and think for yourself.

Personal Science Week is delivered free each Thursday; paid subscribers can also access our Unpopular Science series, including our recent look at cheating and plagiarism by professional scientists.

Please contact us if you have other topics of interest, ask informally in our chat, or leave a comment.

Reviewing the labs with Dr. Goodenowe is something I encourage to learn the granular details and gain more insight . He has been really helpful to my patients and a biomedical scientist. I would call him up. I have taken his plasmalogens personally and they really have helped with focus and cognition.

Thanks for going to the trouble and expense of performing this experiment on yourself.

Alzheimer's is a multifactorial condition with no one root cause. There are different risk factors, among which two of the more important appear to be APOE-4 status and insulin resistance, and Alzheimer's is referred to by some researchers as "Type 3 Diabetes" for the latter reason. I'm currently reading a book on homocysteine levels, which are also linked. Human biochemistry is so complicated it's probably impossible to have a comprehensive understanding of all of it.

You may have seen in the news recently a report of a study published in the The Lancet that high HDL levels correlated with a greater risk of Alzheimer's. I personally have extraordinarily high HDL, and was motivated to spend some amount of time thinking about this. After a period of consideration, one of the things I realized was that in order to make my HDL levels go down, two actions that might help to do so would be to quit exercising and to dramatically increase my consumption of refined carbohydrates, in other words, to become much less healthy.

One of the authors I like but am hesitant to recommend because I think he is erratic and has a bit of an ego is Malcolm Kendrick from the UK, a pro-saturated fat, anti-statin drug person (he is an MD). One point he makes is that death can never be prevented, only delayed, and once you die of one thing, you can't die of something else. He also focuses on total mortality rate - a key takeaway from his work is that the highest total mortality rate for both men and women is seen with total cholesterol below 160 mg/dL. Why would this be, you ask? Well, low total cholesterol does imply low HDL, and there is data supporting low HDL as a risk factor for developing heart disease. That's why it was included as one of the five criteria for metabolic syndrome. Total cholesterol is not part of that assessment.

Anecdotally, Tim Russert of "Meet The Press" had a total cholesterol level of approximately 105 when he died, with an HDL of 37. He is certainly a data point in that high mortality range, and he also did not live anywhere near long enough to develop Alzheimer's Disease (he was 58 when he died).

Looking at the mortality rates from the study Kendrick reports on, a meta-analysis involving over 600,000 people done in the early 90's, the "sweet spot" for total cholesterol is actually right at 200 mg/dL. The lowest total mortality rate for men was seen between 160-200, and the lowest for women between 200-240. As is, lab results for total cholesterol are routinely flagged as "high" beginning at 200 mg/dL. My own total cholesterol was 227 mg/dL last time it was checked, and it was flagged. While I know this is absurd, most people, including perhaps the majority of healthcare practitioners, do not.

Back to Alzheimer's Disease, in the case of the associate from the site I work at who died suddenly last year at age 56 from a cardiovascular event related to a terrible diet and lack of exercise, I would point out two things: 1) he probably didn't have a very high HDL, and 2) he did not get anywhere near old enough to develop Alzheimer's.

I would contrast him with my mom, who is very healthy at age 80 and has an HDL of 99, which would qualify as "high" in the Lancet study. She will likely easily live to age 85, probably 90 or more, and the risk of developing Alzheimer's increases dramatically with age - it is about 50% at age 85+. Her high HDL is indicative of her health in general, and her healthy lifestyle has simply caused her to live long enough to have the opportunity to develop Alzheimer's at some point.

I think that performing thought experiments like this can be beneficial in helping to understand the actual elements that may be driving disease states. What is not helpful is jumping to conclusions - cholesterol is "bad;" thus, we shouldn't eat eggs or other high cholesterol foods. However, I believe that humans are naturally fearful and superstitious, and this is exactly what people do.