Personal Science Week - 231228 Citation Plagiarism

Stealing somebody's citations without confirming the original source

Personal scientists use science for personal, not professional reasons, so plagiarism isn’t normally at the top of our worries. Of course, when publicly discussing your work it’s only polite to acknowledge others’ contributions. But is this just about being mannerly?

This week we show some examples of insufficiently researched attribution, and why you should dig deep into citations, even if you’re the only one who will ever see it.

Personal science isn’t normally concerned with who gets the credit. If an intervention works, it works, and we don’t care who came up with the idea. Unlike professional scientists, who obsess with declaring their conflicts of interest, we’re not going to dismiss an idea just because of how it was financed or who else stands to gain. If you sell me a diagnostic that concludes I need to buy your pack of supplements, I’ll be skeptical about your real motives, but I’m skeptical even if you don’t try to sell me something. Open-minded, but skeptical. That’s just how we do things.

Long-time readers might remember Personal Science Week - 22 Sep 2022 where we described the Zotero app and how it can be useful to keep track of the various sources you are using. The commercial alternative, Mendeley, is good too but not worth the money or lock-in if someday you want to move to another system. To find useful scientific papers in the first place, I’m continuing to find value in Elicit, which uses a pretty good AI semantic search to help find academic papers more efficiently than other search engines.

Insufficient citation

Often the problem isn’t lack of a citation per se, but rather the laziness of an author who choses to cite something because everyone else does. The best example involves the purported health benefits of spinach.

The 2014 paper by Norwegian researcher Ole Bjørn Rekdal, Academic Urban Legends digs into the details of how it came to be general knowledge that spinach is good for you because it contains lots of iron. This entire article is so good that we at Personal Science Week do hereby give permission to our readers to skip our issue this week so you can read the entire thing. Seriously, you will not be disappointed.

The article begins with this quote:

The myth from the 1930s that spinach is a rich source of iron was due to misleading information in the original publication: a malpositioned decimal point gave a 10-fold overestimate of iron content [Hamblin, 1981]. (Larsson, 1995: 448–449)1

We can’t do justice with a summarization because, as you’ll learn, each attempt to uncover the true source of the myth leads to additional myths and counter-arguments that show how difficult it can be to find the truth about anything when you must rely on other sources. The title “Academic Urban Legends” is appropriate, especially when you realize that this is just one fact that happened to draw enough attention to receive some deep analysis. What about those other headline studies that are trusted based on little but the word of the author?

Too good to fact-check

Many ideas are widely circulated because they “prove” something that everyone wants to be true. A good example, which you’ve probably heard repeated countless times is the concept of “blind auditions” as a way to increase the number of women accepted into elite orchestras. Absolutely nobody thinks an inferior player should get the job just because he’s a man. Unfortunately, it looks like men tend to win at the auditions more often — even when the judges are female. Since nobody wants to consider the possibility that this disparity could be the result of anything but (unconscious?) discrimination, a study that “proves” how to correct the disparity will get attention.

The idea is that judges — even the most well-meaning female judges — tend to give higher scores to men, presumably due to subconscious bias. It makes sense that acceptance rates for women would therefore go up if the auditions are given anonymously so the judges can’t tell the sex of the performer. In fact, this was “proven” by Goldin and Rouse in a highly-cited paper that concluded:

Using data from actual auditions in an individual fixed-effects framework, we find that the screen increases by 50% the probability a woman will be advanced out of certain preliminary rounds. The screen also enhances, by severalfold, the likelihood a female contestant will be the winner in the final round.

Few, if anyone who cites that paper bothered to read the caveats that concluded the effect is not statistically significant:

Women are about 5 percentage points more likely to be hired than are men in a completely blind audition, although the effect is not statistically significant. The effect is nil, however, when there is a semifinal round, perhaps as a result of the unusual effects of the semifinal round. The impact for all rounds [columns (5) and (6)] is about 1 percentage point, although the standard errors are large and thus the effect is not statistically significant.

The authors made their bold headline-grabbing claims, not from the data but from “the weight of evidence”. The study was never replicated — who would want to risk finding a different result? — so it keeps getting repeated over and over, as though it’s fact.

This is just one example of an interesting, actionable conclusion you probably assume was based on “science” but turns out to be much shakier when you look into the details. Once again, the moral of the story is: be skeptical, especially if it appears to prove something you want to be true.

More things to try

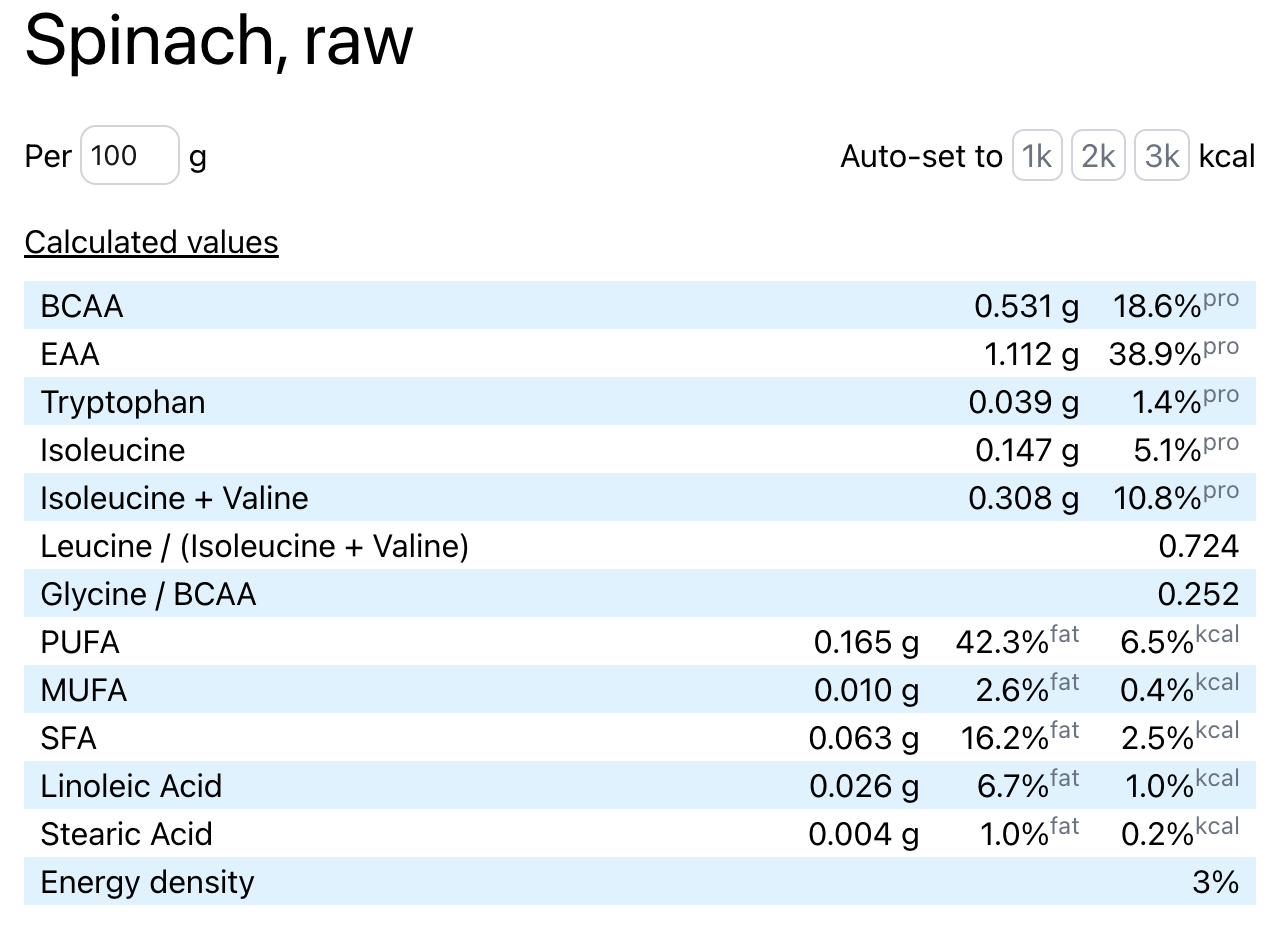

Speaking of spinach, if you want to calculate food nutrition, we like the calculator at the site exfatloss. It’s an aggregator site that pulls data from the USDA nutrition database with more detail and customization than you get from other (free) sources. The SlimeMoldTimeMold interviewed the exfatloss author for some insights on a quantified approach to weight loss.

I’ve been following the wellness app January.ai since their early beginnings as a microbiome test company. They’re backed by Stanford’s Michael Snyder, whose genetics lab is at the forefront of self-tracking for personal health. Although their underlying science seems to be at least as good as DayTwo, Viome, Levels Health, and many others, somehow January never caught on. Now they’ve introduced a new free version of their glucose tracking app. They claim to be able to predict your glucose spikes without wearing a CGM. I ran into some bugs trying to get it to work for me, but I’m sure they’ll be fixed soon. iPhone users can try it, now, at January | Eat Well + Thrive on the Apple App Store: Let us know what you think.

About Personal Science

Listen to experts, but be skeptical. That’s the idea behind Personal Science, where we use the techniques of science to understand and solve personal questions. Often, but not always, Personal Science involves quantitative or statistical reasoning based on self-collected raw data, but the overall thought processes can apply to every aspect of daily life.

Personal Science Week, delivered each Thursday, is free. Paid subscribers can also read our series on “Unpopular science”, including our post about unconventional studies you can join. Please contact us if you have other topics of interest, ask informally in our chat, or leave a comment.