Personal Science Week - 231207

Languages of politics and science

Science is one of many ways to understand the world, a point that personal scientists should especially remember.

This week we offer some thoughts about why facts can be interpreted in different ways to reach different conclusions, plus our Personal Scientist of the week.

Economist and (our highly-recommended) podcaster Russ Roberts, in wondering how experts can sometimes fail so spectacularly, says:

sometimes we are particularly vulnerable to overconfidence if we think we are using “science” and … lots of math behind it that made it look scientific. One advantage to going with your intuition is that you might be more likely to doubt your intuition than a scientistic tool and that such humility might protect you from catastrophe. Cutting edge tools can lead to hubris.

His fellow economist Arnold Kling proposes “three languages of politics” to explain how a news source that reports indisputable facts can still mislead readers. Kling suggests that there are three kinds of “lenses” through which people can view identical facts with different conclusions. Progressives tend to view across “oppressed vs oppressor”, conservatives tend toward “civilization vs. barbarism” and libertarians see “freedom vs. authoritarianism”. Each lens can present perfectly valid and consistent facts that will remain unconvincing to somebody with another lens.

A news source with the “oppressed vs oppressor” lens can say, truthfully, that Julius Caesar’s armies brutally slaughtered tens of thousands of children during his 58 BC invasion of Gaul. But what if the typical soldier was a boy of 16 or 17? Though those killed are technically children, this “fact” is hardly the whole story. Sometimes being under-informed is worse than being mis-informed.

The other “lenses” can present facts that similarly miss crucial parts of the story.

It’s easy to see how this can apply to science, including personal science. How do you inform your takeaways from a study that you haven’t personally verified or replicated? The social sciences, including economics and psychology, despite their interest in quantitative techniques, can never hope to bring the kinds of testability we use in physics. The fields of medicine and biology, too, deal with the impossibly complex world of the human body and its interaction with the poorly-understood world of viruses and more. It’s the ultimate in naiveté to hope we can bring physics-level certainty by simply invoking “science”.

Yet too often people use the word “science” as a synonym for truth, as though attaching a statistic makes one claim more valid than another. The New York Times notes, correctly, that Florida’s death rate from COVID was 43% higher than California’s. But the two states have vastly different populations and it is also a fact that adjusting for age and comorbidity California’s death rate was 34% higher than Florida’s. But facts are true, but when presented in isolation each statistic can be worse than not having it at all.

We’ve referred previously (in PS Week 221229) to Michael Crichton’s point that there are three very different senses in which people use the term “science”:

Nature’s beauty and wonder

Technology and its engineering-driven benefits

Rigorous and systematic pursuit of the truth

If these constitute different “languages”, I’ll state upfront that I want to use the third sense – I want to know the truth. The beauty of nature, or the miracles of technology are perfectly laudable interests, but truth is a language all its own.

Personal Scientist of the Week

MeasuredMe, who describes himself as “Minimalist. Self-Tracker. Data Scientist. Investor.” has posted his self-tracking history since 2012. He was active at Quantified Self events in the early 2010s but his interest gradually shifted until 2019 when, as he puts it, he “shifted from tracking everything to tracking only the things that matter”.

Personal scientists are always interested in quantitative data, which we eagerly analyze using whatever tools we have at hand, whether it’s Excel, a sophisticated programming environment, or ChatGPT. But at some point, it’s important to remember that the purpose is not to track, but to understand. As the uber-quant Gwern says, “QS is not (just) data gathering”.

He published the source code for his dashboard, which though not currently up-to-date is a nice starting point if you’re considering something similar.

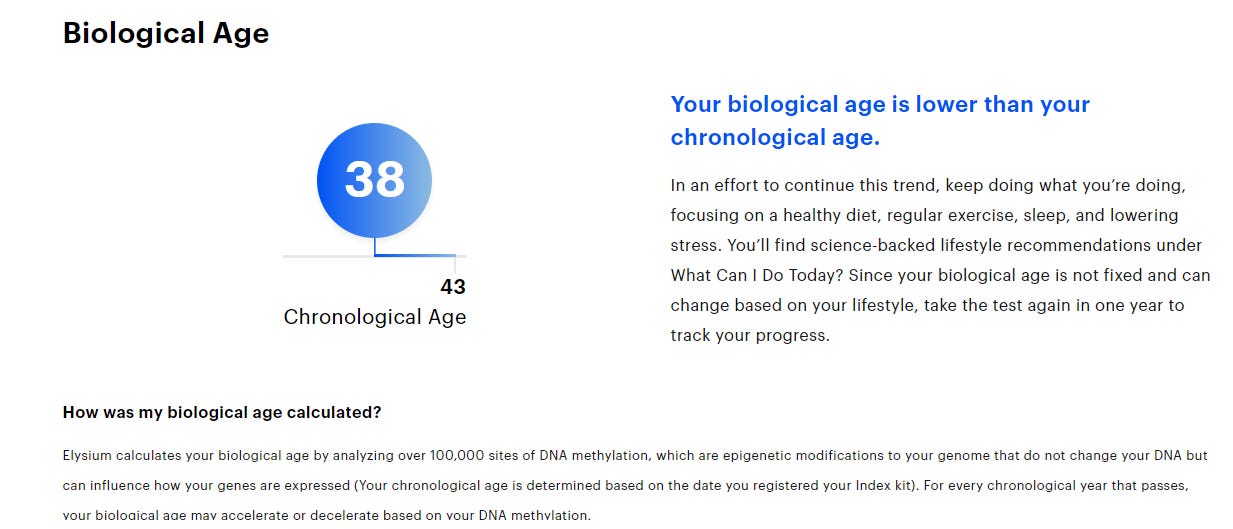

Oh, and speaking of biological age, newer readers should review our reasons we’re not impressed with Bryan Johnson’s Longevity “Blueprint”. He gets lots of publicity, and we admire his interest in trying new things, but if he’s not interested in honest feedback from others, then he’s not a personal scientist.

About Personal Science

If you’re looking for productivity or health tips, there are better sites than this one. We are a short weekly summary for people who like to study the in-depth consequences of what it means to live a life oriented around science.

Personal Science Week, delivered each Thursday, is free. Paid subscribers can also read our series on “Unpopular science”, including our most recent with links of recent interest. Please contact us if you’d like to reach us directly, ask informally in our chat, or leave a comment.