A registered dietitian who claims the best diet is … go ahead and eat whatever you want.

This week we’ll consider some ideas a personal scientist should keep in mind while evaluating dietary advice.

Shena Jaramillo, MS, RD at her website Peace and Nutrition promotes “intuitive eating”, a philosophy that claims food and body sizes shouldn’t come with value judgements. Food is food. Words like “healthy” or “bad” are irrelevant.

It’s easy to malign the idea as yet another example of cultural decadence: weak-willed Gen Zers as snowflakes who will melt away when triggered by threatening news. But I think there is a kernel of truth in the basic idea – that humans are designed to eat and that, as omnivores, our bodies can handle the whole smorgasbord of edible options.

Think of a “decadent” food you enjoy, and imagine if that were the only food you could eat. Everyone reaches a point of satiety where we simply can’t take any more. Even the most unhealthy eater you know — somebody who survives on pepperoni pizza, or sugar donuts — will at some point say “enough”.

The point is that your body has an intuitive understanding of what constitutes “too much of a good thing”. Your body craves a certain amount of variety and, well, health.

Most nutrition research is wrong

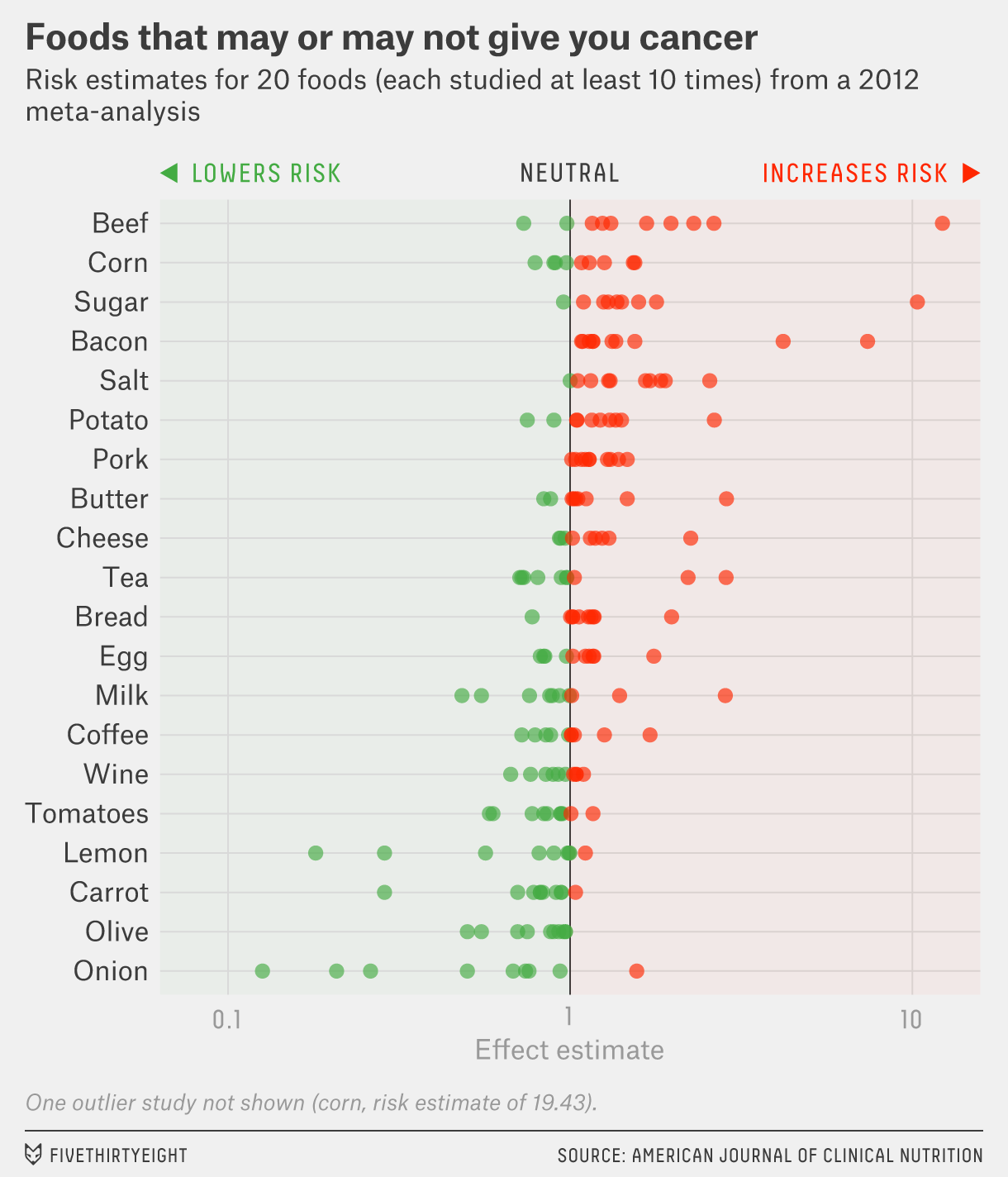

Here’s my favorite chart, based on a clever review originally published by Stanford’s John Ioannidis, among the most-cited researchers alive, who repeatedly demonstrates the sloppiness of statistics and why so many studies fail to produce the same results when tried again. He has given up on nutrition “science”, concluding that nobody should bother with most nutrition research because it’s virtually impossible to conduct accurate studies. The site Fivethirtyeight produced this chart and an accompanying discussion that is well worth the read.

Any personal scientist who bothers to read popular headlines about food and health knows that virtually all of these studies are a waste of time.

Like this recent one from the New York Times: Are Low-Fat Dairy Products Really Healthier? After decades of research, nutritionists are unable to show that low-fat milk is better than regular milk — and in fact may be worse. If you’ve been around for a while, you’ll remember similar “research” that vilified eggs. Transfats, now universally condemned, were recommended by doctors well into the 1990s.

Back in PS Week 22 Jun 2022 we discussed one of the reasons these initial headlines often turn out wrong: initial studies tend to be confirmed by people who are already healthy-minded, but once all of society adopts it as a“mainstream consensus”, the lack of real benefit becomes apparent.

Don’t trust food labels

We wrote about Food Tracking in PS Week 230608 because of course the best way to learn which foods are good for you is to study it yourself.

But you’ll have to keep in mind that food labels themselves are sometimes off by as much as 25% according to various studies summarized in BodyBuilder Magazine.

Product manufacturers, not the government, have the biggest incentive to produce nutritional labels that tout the latest research or fads. That was one of the takeaways from a long report by the USDA “Beyond Nutrition and Organic Labels — 30 Years of Experience with Intervening in Food Labels”. The 90-page report summarizes the history of food labeling laws (see the nice appendix for a list), and gives some of the lessons learned from previous government initiatives around organic, country-of-origin labeling, and more. Written by government bureaucrats at the front lines, the chapter on how they approach GMO labeling issues is especially interesting because it shows the tension between setting standards and letting the market figure out the best way to offer labeling.

Maybe we’re smarter than we think?

But what about the obviously “bad” foods? We’ve all heard that the Standard American Diet is high in sugar, salt, and fat because we humans evolved to seek out flavors that are calorie-dense. Out on the savannah, our ancestors tended to survive more when they took advantage of rare but efficient sources of energy. Today, the story goes, Big Food capitalizes on this weakness to tempt us into eating too much.

Food writer Mark Schatzker, author of The Dorito Affect, thinks people and animals are hard-wired to prefer the nutrients their bodies need at the time. He points to numerous hints that we know more than we think. Babies, for example, when given a choice will gravitate toward a well-balanced diet. One of the first symptoms of scurvy noticed by 18th Century long-distance sailors was a strong craving for fruits and vegetables. If you own a pet, you’ll notice that animals often appear to know that it’s time to eat a particular food.

UK researcher Jeff Brunstrom worked with Schatzker to show how, in hundreds of tests, people unknowingly pair foods with complementary nutritional profiles.

In other words, trust yourself.

About Personal Science

If you’re looking for productivity or health tips, there are better sites than this one. We are a short weekly summary for people who like to study the in-depth consequences of what it means to live a life oriented around science.

Personal Science Week, delivered each Thursday, is free. Paid subscribers can also read our series on “Unpopular science”, including our most recent post about unconventional studies you can join. Please contact us if you have other topics of interest, ask informally in our chat, or leave a comment.

There is a bit of conflation here in regard to the idea of craving what your body needs and misconceptions about what foods are actually unhealthy. The sodium in salt, as an example, is an essential nutrient animals can't live without, while sugar (sucrose) is a tasty substance in no way necessary for human survival. Sugar cane originated from the vicinity of New Guinea, and the ability to tolerate large quantities of it is simply not a natural part of the human genome. I observe some people with superior genes do appear to have the ability to consume considerable amounts with little to no ill effects, while many others (I am in this group) cannot.

Genes play a critical role in health, probably longevity, too, and it's easy to take them for granted if you have good ones. In The Art and Science of Low Carbohydrate Living (Volek and Phinney, 2011), the authors remark that any one person's DNA is approximately 99 - 99.5% identical to that of any other person's, with the differences mostly related to copy number variants and single nucleotide polymorphisms. In the former case, for example, a person from a culture with a history of eating a high starch diet, as in much of Europe and Japan, may have more copies of the gene salivary amylase (amylases break down starches) than a Yakut in northern Siberia with a traditional diet heavy in meat, dairy, and fish.

Similarly, people from cultures with a history of eating dairy products may have a greater incidence of single nucleotide polymorphisms allowing them to continue producing the lactase enzyme into adulthood. The ability to do so is not a natural part of the human genome - it had to evolve in response to environmental stimuli.

No human culture has had long term exposure to the amounts of sucrose currently being consumed in the United States - sugar was simply too expensive to be available to the masses in other than tiny quantities before the establishment of sugar plantations using slave labor in the Caribbean and South America in the 1600's. The application of fossil-fuel energy and mechanization since then has made it much, much cheaper and available in mass quantities today.

As I indicated, genes play a critical role in all of this. I worked with a guy my age in the early 2000's who did not survive to age 40. I observed he had a terrible diet, and he also seemed likely to have very, very bad genes, as he was the unhealthiest person I've ever known. Furthermore, the medical advice he was being given at the time did not seem based on sound science and an understanding of human biochemistry, and thus apt to genuinely be helpful, given the knowledge I have today.

I close with one more example - I worked with the person in the obituary below, who died suddenly earlier this year. He also appeared to lack the superior genes some people have, and his may have been unusually bad. While highly intelligent, most people perceived him as a snack food junkie, unable to resist large quantities of doughnuts, in particular. If he had been blessed with better genes, I think he might still be alive, but in the event, as a British writer might be inclined to put it, he isn't. It was a shock to his family, and I know it must have caused them an extraordinary amount of pain.

https://www.schrader.com/obituary/douglas-niermeyer