Quantitative answers to personal science questions are only as good as the methods used to collect them. Unless your tests accurately reflect the underlying phenomenon, you won’t learn anything useful.

This week we look at some disturbing facts about common lab tests.

In PS Week 231026 we noted that our results from an at-home urine test were significantly different in the evening than in the morning. We also reminded readers that the CLIA lab certification process, while consistent for a specific lab, doesn’t imply that results will be comparable across labs. But surely the common blood tests we get from our annual physical are reliable, right?

Long-time readers know that we’re big fans of the at-home blood testing company, SiPhox Health, which sells a $95/month subscription that gives you results from about 20 blood markers, including all of the common ones used in most physical exams. Plus you get insulin, sex hormones, and Vitamin D. LabCorp will charge upwards of $400 for all those tests, and you don’t even have to leave your house.

At the time of my review, I noted that the SiPhox results mostly matched what I got from a LabCorp test I took at the same time — with one notable exception: SiPhox said my Vitamin D was a healthy 45 ng/mL, but LabCorp said I was well under 30 ng/mL — considered dangerously low. If LabCorp is right, then I probably need to urgently increase my Vitamin D, but the SiPhox result says the opposite. Who’s right?

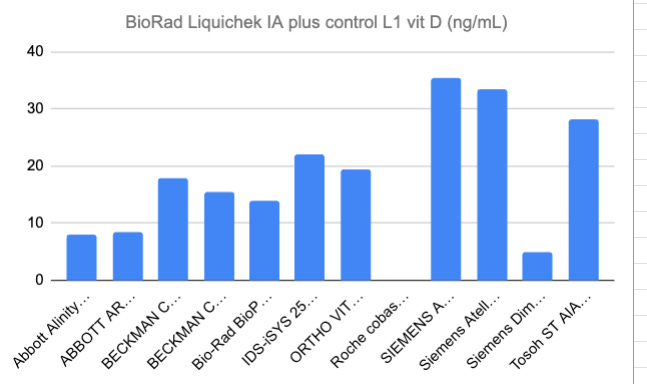

But then SiPhox CEO, Michael Dubrofsky, showed me a chart from the life sciences company BioRad. When a lab wants to create a new diagnostic, they’ll want to test it against a known control, such as the BioRad Liquichek, which is essentially a chemical compound guaranteed to be a pure form of whatever you are targeting. I was shocked to learn that these control chemicals, while consistent for a single lab, can show significantly variability across different labs.

Remember: a lab that has passed CLIA inspection is legally allowed to claim they are measuring something so long as they do it consistently. CLIA does not make claims about whether that measurement is actionable one way or another. Different labs can pass CLIA inspection even with dramatically different results on the same specimen.

In fact, that’s what happened here. When the control was compared against a broad set of identical blood serum, the results are highly variable. The same specimen yields a dangerously-low 10 on some labs, and a comfortably-health 30+ on others, with everything in between. Whose results can you trust?

This situation is more serious than a simple question of which result is “correct”. Remember that this high variability applies to scientific research labs too. If a large peer-reviewed study makes a health claim, you don’t know if that applies to you unless you know exactly which lab performed the study. In the case of Vitamin D, where the consensus seems to be that anything under 30 ng/mL is “low”, you can’t compare your own results unless you know precisely which lab did the analysis.

I don’t know how much of an issue this is for other types of tests. Lipids like cholesterol, I’m told, are far easier to measure than a complicated molecule like Vitamin D, so there is less leeway in how a lab reports its results.

Nevertheless, consider my skepticism raised even further the next time I’m tempted to change my behavior strictly on the basis of one test result.

It’s true for cholesterol too

This is as good a time as any to remind readers of a fantastic research article published in 2019 by Azure Grant and Gary Wolf with support from Quantified Labs. Twenty volunteers recruited from the Quantified Self community took multiple measurements of their blood cholesterol at designated intervals throughout a single day. The result:

Within-a-day variability resulted in 47% of individuals crossing at least one risk category (i.e., low risk to moderate risk, or moderate risk to high risk) in TC (Total Cholesterol) or HDL-c, while 74% of individuals crossed at least one risk category for triglycerides (n = 19 participants for all within-day measures). All individuals crossed at least one risk category in at least one output.

In other words, if you make judgements about your cholesterol based on a single measurement, it’s very possible that you are misjudging your risk category.

As with the Vitamin D example above, keep in mind that the vast majority of research studies — including virtually every one that you or your doctor is quoting — base their conclusions on participants who have been tested a single time under specific conditions.

The conclusion: be skeptical, ask questions. Don’t assume that whatever you read in the peer-reviewed literature applies to you.

About Personal Science

Professional scientists are busy doing everything that anyone must do when they have a job. They have bosses who don’t always understand or appreciate them, colleagues who are trying to outcompete them for promotions, and the many inevitable tradeoffs that come when you do something in order to make a living.

As a personal scientists you’ll have your own biases, but with one advantage over the professionals: Nobody cares more about your health or well-being than you and your loved ones. Use that to your advantage: perform your own experiments, ask questions, don’t be afraid to try new things.

As always, please let us know if you have other topics you’d like us to cover, or leave a comment.

Labs performing tests typically provide you with reference ranges for their tests. Labcorp and Quest for example have the same test method and reference ranges for vitamin D, but use different test methods with slightly different reference ranges for testosterone. I'm guessing SiPhox still needs to establish the reference ranges for whatever it is they are doing.

Like blood sugar and blood pressure, cholesterol (and related markers) changes throughout the day, so it would be useful to both know your "fasting" levels as well as having more continuous data.

Total cholesterol is an ambiguous test to begin with, as the highest total mortality rate for both men and women is seen below 160 mg/dl. I think it's crazy to flag 200 as high as many labs do, as that is actually where you want to be. We should really be focusing on HDL-C and triglycerides, and both should be taken fasting.

I use fasting triglycerides divided by fasting HDL as a rough estimate of LDL particle size. That ratio ideally should be below 2.0. Lower ratios indicate larger diameter LDL, which is thought to be more benign. I know people with ratios below 1.0, even below 0.5, which indicates to me a relatively low risk of ischemic stroke or heart attack. However, such a person could still have high BP and be at considerable risk for other serious health conditions, such as kidney disease or the type of stroke associated with bursting blood vessels.

An example of a poor ratio would be fasting triglycerides of 250 and fasting HDL of 50, a ratio of 5.0. I would be concerned about the condition of the coronary arteries of such a person and would suspect possible atherosclerotic lesions, with considerably increased cardiovascular risk.

I've had very consistent results with the provider I use and have no particular reason to doubt my lab results, but there is no doubt variability among labs.