Personal Science Week - 230706 EMF

Measure the electromagnetic fields around you

We are surrounded by radio waves — WiFi, mobile phones, bluetooth. Our public officials and professional scientists insist it’s perfectly safe, but that’s not good enough for Personal Scientists. How can you check for yourself?

Our neighborhood is blessed with good mobile phone coverage, which is a Real Estate Speak way of saying we live near several large cell phone towers. When our teenage daughter began to suffer migraine headaches, I wondered if some of that electromagnetic radiation might be related. Her window, after all, was directly facing one of the biggest towers in the neighborhood.

Electromagnetic Fields (EMF)

If you’re tempted to be scared about the flood of waves generated from man-made equipment, it’s important to remember that EMF is just a form of energy. The waves from your devices are fundamentally no different than the visible light people have enjoyed from the sun forever. In fact, of all the types of energy exposure you regularly endure, sunlight is by far the most powerful. So keep that in perspective before worrying too much about the invisible forms of light.

But just as too much sunlight can be dangerous, EMF carries known health risks too. Innumerable studies attempted to calculate “safe” levels, and as with most subjects involving health, it should be no surprise that there is wide disagreement.

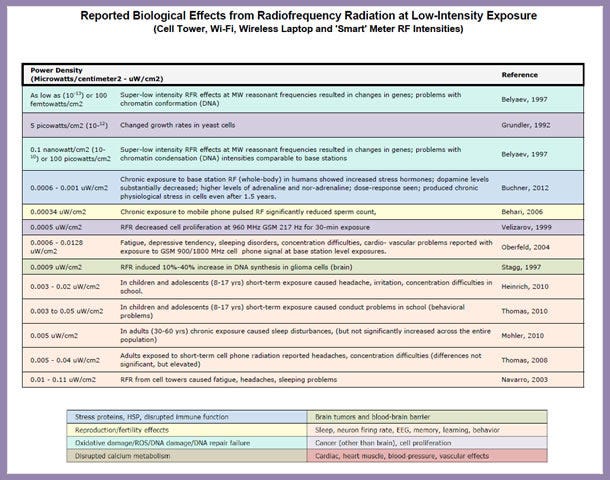

An organization called the Bioinitiative Report summarized the research in a handy 11-page chart you can download from their website:

You might think that government regulators, after carefully studying all the various studies, would come up with safety guidelines that are roughly similar. Alas, the regulations are all over the map internationally. For example, on the 1800 MhZ band used by mobile phones and WiFi routers, the US FCC’s “safe” limit is 10,000 times higher than Italy’s. (Freedom-loving American readers will be happy to learn that this is true for nearly all standards, where I found that the US is often orders of magnitude more permissive than anyplace else).

As every Personal Scientist knows, what the government considers safe and what is in your actual environment are two different things. To learn what works for me, I had to find equipment to measure for myself.

Measuring EMF

The best consumer-grade EMF device is the Trifield TF2 ($186 on Amazon). You can find other units, some for less than $20, that claim to detect the same fields, but for reasons I’ll explain, I don’t trust them. You can also get fancier models that will log your results to a PC, but the Trifield TF2 is a proven workhorse used for years by many experts I trust. Sure, an export feature would be nice — imagine making a color-coded map of the inside of your house — but for my first pass I care more about accuracy.

And indeed, when I measured the radio frequencies (RF) in my house, I found the highest levels right there on the pillow where my daughter sleeps! It even exceeded the Trifield’s detection limits!

I tried several areas throughout the house and wrote the numbers in a simple spreadsheet. I found that the numbers bounce around quite a bit depending on the direction I’m facing face and how close I am to walls or other objects. My spreadsheet includes both the maximum and minimum I recorded at each location.

When I found super-high numbers, I was usually able to immediately find the problem. For example, a simple electric fan turned out to be one of the highest emitters in the house — even when turned off! I unplugged it and the level plunged to near zero. Similarly, you might be surprised how much EMF comes from your home washer and dryer. Ours has an off switch that previously I thought was no big deal; when the machine isn’t running maybe it uses a tiny bit more electricity but otherwise who cares? Well, turns out that for RF measurement, it matters a lot.

The Phone Company Investigates

Upon seeing these high values on my Trifield, I contacted AT&T, the company that operates the cell tower nearest my home. To my pleasant surprise, they were very cooperative and immediately sent an investigator to our neighborhood to do a preliminary assessment. As you might expect, urban cell towers are inspected regularly (and independently, by a third party) and compiled into an “Maximum MPE Report”. This tower had recently been converted into a 5G tower, with the high scrutiny that involves, and had passed all tests. So the company was quite concerned when I appeared to have data showing it might be unsafe.

Incidentally, the tech was shadowed by an attorney who very politely responded to every question I could think of, eagerly following up at regular intervals to ensure I felt comfortable with their answers. For example, when I was told that that the MPE report is confidential for competitive reasons (because it includes specifics relating to how much power they generate and the customers served), the attorney overruled company policy and got me all the reports I wanted.

AT&T claims to follow FCC Rules that include this chart (p. 67):

For example, at 700 MHZ, look at the right hand column for the row “300-1500”, and the Power Density column (1500). This is the maximum allowed. Divide the frequency in MHz (700) by 1500 to get 4.6 mW/cm2. The Trifield TF2 measures in mW/m2, so any measurements less than 4.6 should be “safe”.

Warning: Be very careful with units when you study these charts: you may find yourself all worried (or complacent) about your results, only to discover you’re off by an order of magnitude. Use the calculators at Powerwatch.org.uk and triple-check your work.

I’m Safe

After showing the techs my Trifield results and going over all the numbers with me, I still had some questions. At that point, the attorney arranged for AT&T to send one of their best radio engineers up from California to carry a professional-grade EMF detector to study my neighborhood and the inside of our house.

Dave convinced me that I was incorrectly interpreting my Trifield T2 results and its implications for safe limits. His device is much more sensitive, and isn’t thrown off by spurious signals. When I walked around and through the house with a professional, together we were unable to find anything that exceeded 1% of the FCC maximum limits. Even when he walked outside and pointed directly at the tower, we were unable to find anything that remotely seemed like a threat.

That super-high measurement at my daughter’s pillow? It has nothing to do with the cell tower, and anyway it’s several orders of magnitude below anything ever shown to affect people. Turns out I was misreading the device.

In fact, one reason to avoid those cheaper EMF detectors is that their sensitivity to specific frequencies is so low. The amount of energy that hits your body is a function of the frequency and the power, but most consumer grade devices look over too wide a frequency range, giving a false sense of how much power is actually concentrated in the signal. When measured with proper equipment, it’s pretty hard to find everyday items that come anywhere near the safety thresholds, even by relaxed US standards.

References

If you want to study this for yourself, I found the following resources especially helpful:

IARC Monographs: Non-Ionizing Radiation, Part 2: Radiofrequency Electromagnetic Fields is a (free) 500-page eBook that goes into gory detail about how exposure is measured and detected. Everything you want to know about EMF and what is known about its effects on humans, including cancer.

Bioinitiative.org : mentioned above for its summary of research studies, the whole site is useful, and updated through 2022.

Powerwatch: a UK-based non-profit with detailed discussion including helpful unit conversion calculaters.

The EMF Guy: Nick Pineault describes himself as a journalist who has studied the problems of EMF for years, and his site gives the “we’re-all-going-to-die” point of view. In fact, he even published a book The Non-Tinfoil Guide to EMFs for people who might want to dismiss him as a whacko conspiracy theorist.

Bob Troia (aka “Quantified Bob”) wrote his own detailed study of EMFs in 2022.

About Personal Science

Nullius in verba The 1660 motto of the Royal Society: “take nobody’s word for it” is a good guideline for the rest of us who are curious and want to use the techniques of science to solve everyday problems as we learn more about the world around us.

We publish this newsletter every Thursday, free to anyone who wants to be Personal Scientist. This week we inaugurate a new service, for paid subscribers only, called “Unpopular Science”, in which we dig into ideas that are too controversial or outside the mainstream consensus to discuss in a public forum. We figure if you’re willing to spend the money to subscribe, we’ll trust you to read our most controversial ideas in good faith.

Our first Unpopular Science post is about The Netherlands … and Climate Change.

Please let us know what you think! Meanwhile, if you’re looking for something specific, search our archives or contact us directly.

Haven't tried measuring EMF, but I did once borrow a power meter from the library to check if we have any devices that use much energy while "off". Only offender was a projector.