The food you consume probably has as big an impact on your health and performance as anything else, so of course as a Personal Scientist you’ll want to track and study it carefully. This week we’ll discuss some of the basics.

Having intensively tracked my food intake at various times in the past, I think I’ve settled into some general guidelines that work for me. I use apps and devices, of course, but judiciously. Bottom line: focus on the goal, not the how.

Food Tracking Apps

The “how” is easier with apps, and I’ve tried most of them:

MyFitnessPal is widely used and has the largest food database. Because so many of the entries are user-submitted, it tends to know about items as soon as they’re launched, but the data quality can be variable. No easy export to CSV.

Bitesnap calculates the nutrition of a food based on a photo, but I could never get it to work well. It especially has trouble guessing the portion size.

Some people like Fatsecret, which boasts a huge database and enthusiastic following, but I find it less useful if want to do non-mainstream tracking, like for odd diets or self-experiments. You also can’t easily export your raw data.

and many others…

My favorite app is Cronometer. Although the free version is pretty good, if you are serious about tracking I recommend you start with the $50/year “Pro” version. It has all the essential features:

Enter your food manually or through a barcode scan.

A large database that includes many of the more obscure nutrients that other apps don’t (e.g. magnesium, amino acids, caffeine).

Enter precise time of day (Pro version only)

Distinguish between “Meal” (so you can track a combination of foods) and “Food”, when you’re interested in a single item. This is important for aggregation later.

Export everything to a CSV file for detailed analysis (Pro version only)

And it integrates with most common tracking devices and services (e.g. Apple Watch, or Keto Mojo for ketone measurements)

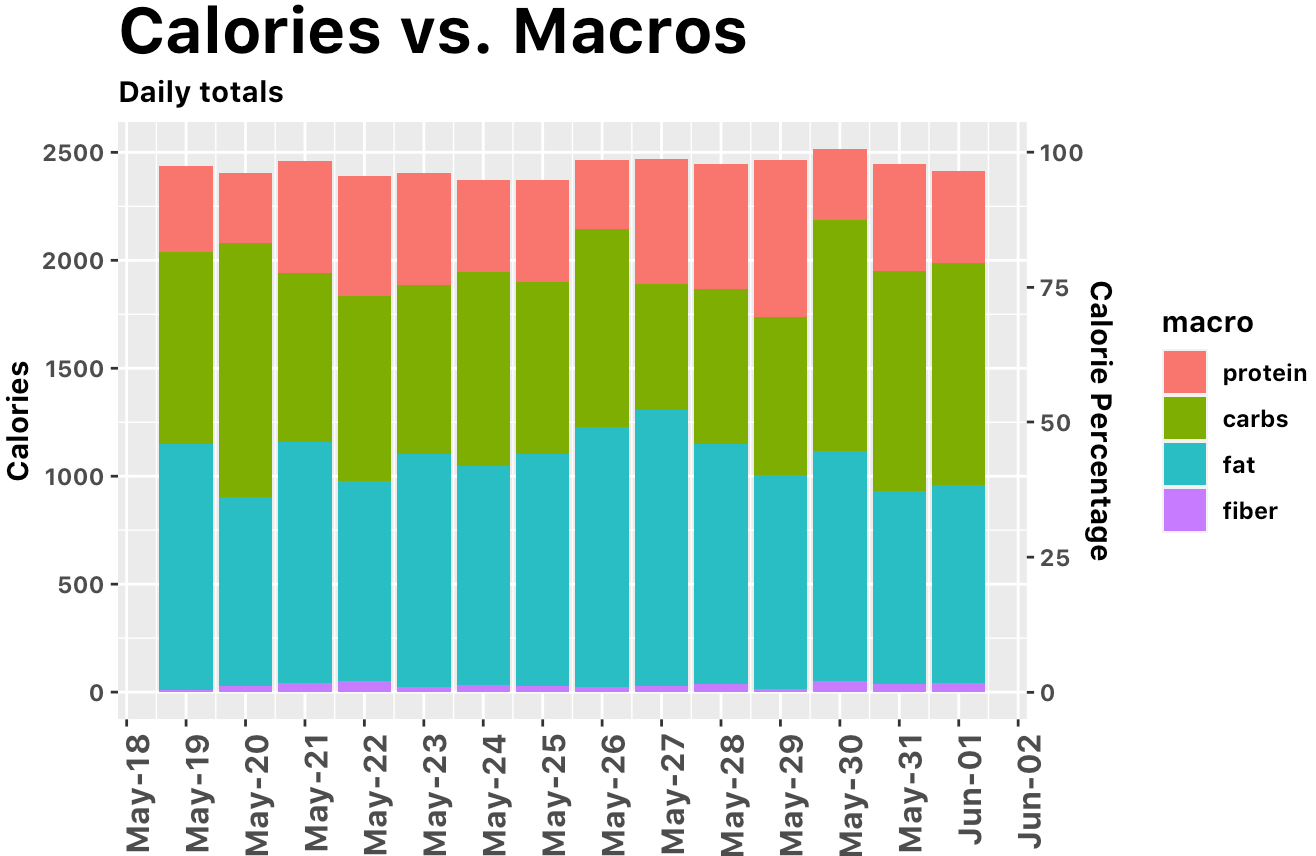

Here’s a simple chart I was able to generate from my Cronometer data:

After having used Cronometer for a few years, I already have a large exported CSV that I can mine for insights and I no longer feel the need to use it every day. But if you’re getting started, I’ve found it perfect for my needs.

How I Track Now

Don’t let yourself be so distracted by data collection that you lose sight of why you’re tracking in the first place. Cool apps and hours of study can be fun, but too many people spend this laborious analysis only to reach obvious conclusions, like “I gain weight when I eat more”.

Instead, I recommend using the app studiously for a few weeks only. But take it very seriously. Use a cheap food scale to carefully measure each item until you get a good sense of portion sizes: you’ll be shocked at the difference between the label’s definition of a “serving” and what you were imagining. Focus on relative differences between foods: Which has more sugar, an apple or an orange? After a while, you’ll get so you can tell intuitively which foods have more calories or sugar or fat.

In my case, now I just keep a very informal journal where I write brief notes about what I ate. A typical day might say: banana, leftover green beans, chicken mole, bread. That’s it. For example, I was able to trace some digestive issues to red meat — something I don’t eat very often. Simply looking back on the last time I had the issue was enough to confirm the cause. Yes, I could have discovered the same thing through a multivariate machine-learning model, but this was a whole lot easier.

Food Tracking Links

Before you take those food apps or the nutrition information too seriously: A New York Times short 6-minute documentary and editorial shows how wrong labels can be. Casey Neistat took normal foods and ran them through an expensive calorimeter — the gold standard to see how many calories an item contains -- to check the accuracy of the labels. In his random sample, he found the discrepancies between the labels and actual calories added up to 500+ calories in a typical day’s eating — the equivalent of a missing Big Mac or a couple of snickers bars. This, on “normal” foods like a sandwich from Subway, a yogurt muffin at a convenience store, a Chipotle burrito, a vegan deli sandwich.

Want to make your own FDA-approved nutrition label? Use Nutrition Pro for $50/month. Or get your own portable Mass Spectrometer from TellSpec to measure the foods yourself.

The Sift App gives a more detailed breakdown of the ingredients on any product. First 5 scans are free, and after that it’s about $3/month.

In previous issues, we discussed an app to answer how processed is your food, an energy balance calculator, and more in the archives.

Events of Interest

Personal Scientists who want to collaborate with others should know about a few upcoming events of interest:

QS Show&Tell: Tracking Blood Glucose with Nutrisense: Tuesday June 13 at 7:00 AM PDT / 4:00 PM CEST (Yes, that’s 7am for people on the West Coast). It’s a private Zoom, so you’ll have to register in advance here. I’m looking forward to this one, featuring Quantified Self co-founder Gary Wolf describing his recent experiments with continuous glucose monitoring.

Reminder: Everyone is welcome to the weekly OpenHumans Self-Research Chats, held Thursdays at 10am PT (18:00pm GMT). It’s a Zoom call and I’m usually there, as are several long-time Quantified Self regulars. For details and notes see their Google Doc.

Your local area almost certainly hosts events that will let you find other personal scientists. Look for events with keywords like “biohacker”, “biocurious”, or even “personal science”. I usually attend the weekly Seattle Biohackers meetup each Saturday morning where I always learn something of interest.

About Personal Science

Personal Science is about using the tools of science for personal, rather than professional reasons. Each week we share tips and ideas we think will be useful to anyone who wants to be a Personal Scientist. Learn more and see our archives at personalscience.com.

As always, if you have other topics you’d like to discuss, please let us know.