Personal Science Week - 23 Jun 2022

Free microbiome tests, food processing, why food fads appear to work, and what I'm watching this week

Microbiome testing

Two (free) microbiome tests I’ve tried in the past week:

NYUFamili gives you a $25 gift card for completing a questionnaire and emailing a gut sample.

Endominance wants to understand the relationship between the microbiome and anxiety. After signing up for their MACO study, I filled out a 100-question survey and received their gut test kit. They’ll pay $40 to participants.

Both organizations say they’ll give me the results of their tests, which I eagerly await and will report when I receive them.

Meanwhile, microbiome company Viome this week launches their latest test, called Full Body Intelligence™. Although I remain intrigued by their science, I’ve had mixed results from the multiple kits I’ve tried with them in the past. As they pass 300,000 users, their recommendations should be getting noticeably better, so I’ll look forward to what this new test brings.

How processed is your food

USDA researchers released a study that concluded, based on surveying 9700 people, that most of us overestimate the quality of our diet. If lack of accurate nutritional information is the cause, maybe it will help to try the food analyzer at truefood.tech. It’s a simple web app that gathers public data about thousands of foods and their ingredients to classify each according to how “processed” it is. The theory is that the closer a food is to its “natural” components, the healthier it is.

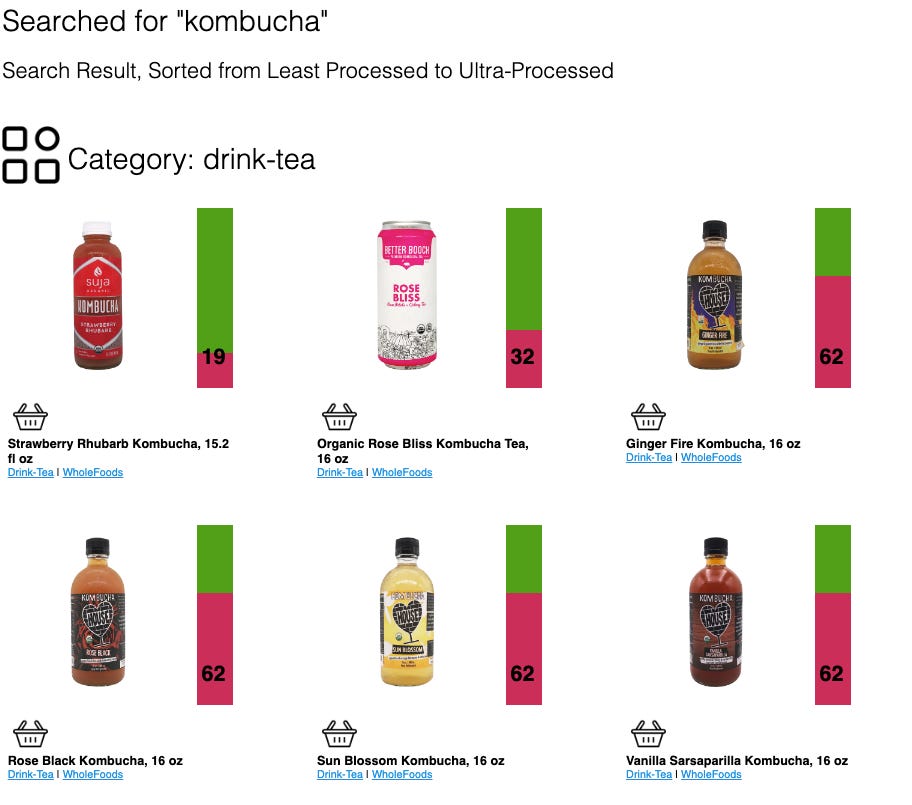

Here’s what happened when I searched for “kombucha” :

Seems odd that the various products would have such wildly different ratings, so perhaps this new tool raises more questions than answers. Still, I appreciate another way to look into the details of how the food we eat is made.

Food “Fads” are often self-selecting

Economist Emily Oster points to another gotcha that can afflict the notoriously unreliable results of diet and nutrition studies: bias in what gets studied in the first place. Professional scientists study whatever they think is of interest to their audience, which is almost always their fellow scientists and the various agencies who fund them. When a specific finding gains attention, even well-done follow-up studies often affirm the original results for the first decade or two. But maybe this is because the type of people who pay attention to the latest research are more health-minded than the rest of the population. In the following plot, the red color indicates the apparent improvement in people who tried Vitamin E the first 5 years after it was widely publicized. Green shows the results for the next five years after that. How could Vitamin E be good for people in the early 2000s but not after that?

She gives many other examples, such as a relationship between coffee-drinking and health. Once a new finding gains publicity, many people latch onto the new idea and it appears to work — for a while. But maybe this simply reflects that the type of people who read and practice the new findings are themselves more health-conscious. In that population, practically any intervention will appear to work. It’s only after decades of knowledge seeping into the wider population that we see the true effect…which is often disappointing, because by then it’s “normal” people.

About this newsletter

What happens when you honestly try to apply principles of science to your personal life? We call it “Personal Science”, a thoughtful attempt to be deliberate in questioning — and testing — the ideas around us.

We welcome feedback! Let us know if you found something helpful in this week’s newsletter, and meanwhile please share with your friends by clicking below.