This is a short summary of ideas and links we think will be interesting to anyone interested in Personal Science, using the techniques of science for personal rather than professional reasons.

This week we discuss a few ideas related to cooking. To a Personal Scientist, a simple kitchen is a sophisticated laboratory. What can we learn?

Experiment with flavors

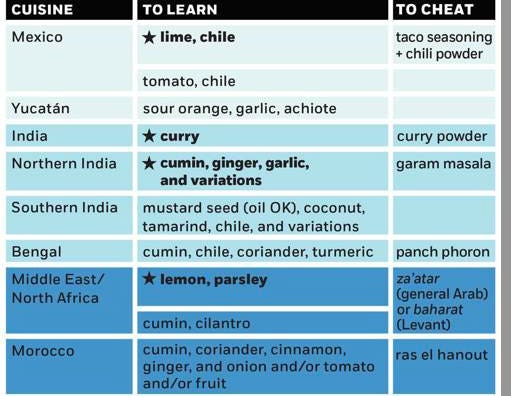

My favorite way to add interesting flavor to any dish is to follow the guidelines in this series of charts from Tim Ferris’s excellent book The 4-Hour Chef. Here’s one sample:

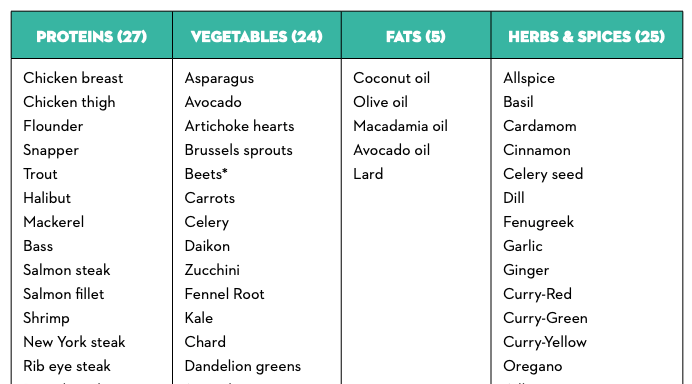

Another way to simplify healthy cooking comes from Robb Wolf’s Food Matrix. Choose one item from each column — it doesn’t matter which one — and you have a simple, healthy meal:

How safe is your food?

We all know that meat should be cooked thoroughly before eating, but why? and says who? Part of the reason is flavor and ease of digestion, but every conventional discussion of meat includes the mandatory explanation that cooking is important to prevent disease. Still, animals eat raw meat all the time. We humans eat raw fruits and vegetables. What’s so special about meat that we think it should be cooked?

In fact, the interior of all animals, including that piece of chicken or beef, is sterile. Animal bodies are carefully designed to protect the interior from pathogenic microbes, which even in the tiniest amounts can cause serious illness and even death once they begin multiplying in the warm, well-nourished interior of a living creature. Unfortunately the exterior of an animal is usually loaded with microbes, many of which are pathogenic. When meat is poked or cut, there is a significant risk that some of those external microbes might land on the meat parts that you eat.

When you buy a shrink-wrapped piece of chicken or beef at the supermarket, you’re getting the interior — i.e. sterile — part of the animal. It’s always possible (perhaps likely) that some microbes slipped into the product somewhere in the processing, so maybe that’s the reason you should cook it? But again, isn’t that true of vegetables as well?

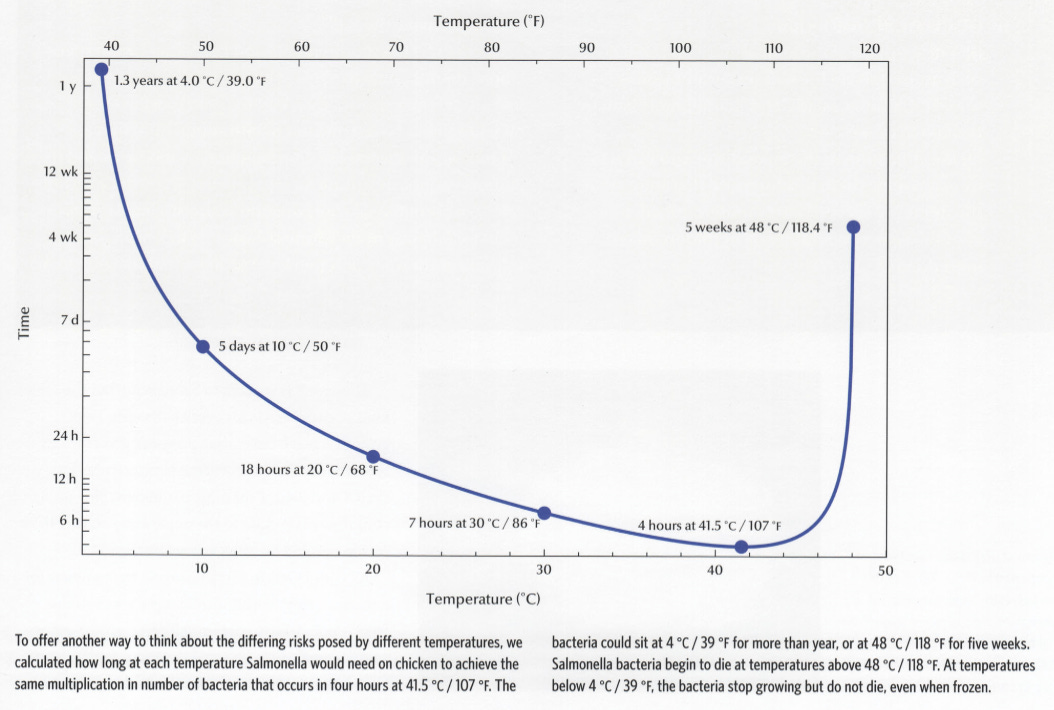

Pretty much all pathogenic microbes die at temperatures above 75ºC (165ºF), which is the origin of the better-safe-than-sorry advice you’ll find in cookbooks. But that’s only if you want to be really, really safe. In fact, microbes stop dividing and generally die at much lower temperatures. When the scientists at Nathan Myrhvold’s Modernist Cuisine Lab tested USDA’s claims about microbe survival, they produced this chart:

In other words, while it may be technically true that pathogens like Salmonella remain alive at temperatures below 75ºC (165ºF), for all practical purposes they stop reproducing long before that, and are essentially inert by 50ºC (120ºC). Ultimately the most important variable is your health and the health of your family members, so you may decide that even this tiny risk is not worth taking. But many foods taste considerably better when cooked at lower temperatures, so keep the tradeoffs in mind too.

Curated Links

Here are a few cooking-related sites that deserve more attention from serious Personal Scientists:

The “Make Everything” blog by Omniafaciat is apparently no longer updated, but includes detailed instructions for making your own fermented (“black”) garlic, a low-cost seedling grow box, and more (much of it is available on Instructables)

Modernist Pantry sells personal quantities of food additive ingredients normally available only to big food companies. For example, looking to increase the amount of fiber without affecting the taste? Try Methocel-50, a $15 pack of which will add 50g of fiber to anything.

The Sourdough Framework is an open-source book that claims to be the ultimate guide for bread-making. Written by a programmer, for programmers, it was widely shared along with other interesting bread-making links at Hacker News.

About Personal Science

Personal Science is the process of using the scientific method to solve problems and get better results on an individual, personal level. Following the motto of the Royal Society, established in 1660, nullius in verba, we take nobody’s word for it. We rely on our own observations and make up our own minds.

This newsletter, published every Thursday, is a weekly summary of a few references we think will be interesting to anyone who wants to be a Personal Scientist.